A disease that severely damages cannabis plants is rapidly spreading across Canada.

The hop latent viroid (HLVd) started emerging on cannabis crops in California as early as 2017 before first being noticed in British Columbia a few years later.

Once isolated to only a few whispers and rumours, it has now spread across Canada, infecting as many as 40% of licensed growers in the country, says Brian Coutts, a Strategy & Business Development Manager at A&L Labs. A&L is one of the few labs in Canada offering testing for the viroid.

“It’s out there more than anyone thinks,” says Coutts. “It was about two years ago now we had our first positive test, and it was in BC. Since then, it’s clear across Canada in every province.”

Coutts says by his estimate, he figures about 40% of cannabis growers in Canada currently have or have had to deal with HLVd, causing major crop losses for big and small scale growers alike.

The viroid both weakens the plant overall, creating smaller, more brittle plants and it affects cannabinoid and terpene production.

“Everyone is chasing that THC number, as they think that’s what the consumers want,” says Coutts, “and the number one problem with the viroid is that it can bring down those THC levels.”

“It’s out there more than anyone thinks. It was about two years ago now we had our first positive test, and it was in BC. Since then, it’s clear across Canada, in every province.”

Brian Coutts, A&L LAbs

One cannabis grower in Canada who has been vocal about his experience with the viroid is Benjamin Padovani, the owner of Treez Botanicals, a micro cultivator in Ontario. Padovani had to recently destroy all his plants, including clones in veg and flower rooms, as well as his mother plants and his entire genetic library, after discovering hop latent viroid.

Although he’s not 100% sure how he picked it up, Padovani says he suspects it was from a batch of clones he acquired prior to licensing. Because Health Canada allows growers to bring in an unlimited amount of starting materials in the form of clones, mother plants, seeds, and tissue culture (basically anything but flowering plants) prior to licensing as part of a one-time transfer, many applicants try to gather as many genetics as possible before they get their licence.

The value of this approach is having a robust and unique genetics library that can help a new grower stand out in the market. But with few controls in place and growers not always testing everything they bring into their facility, the risk of diseases like hop latent viroid or powdery mildew, as well as pests like thrips or aphids, can be a risk.

Issues with powdery mildew are well known in the industry, with—some growers hiding it and others being open about their experience in managing and eliminating it, a process that entails, like with the hop latent viroid and other similar issues, destroying all infected plant matter and thoroughly cleaning the facility.

“I had my genetics for years and never had this issue,” explains Padovani. “But because Health Canada only lets you bring in genetics the one time, I thought that I would do one last push to bring in some more before I was licensed, and I think it came in that way”

“I never bothered testing them and wasn’t careful because you never think it will happen to you. But it happened.”

“I noticed maybe two or three of my plants in one room looked like they had totally different characteristics than all the other plants of the same variety. Then in my second room, I noticed about 30% were completely showing signs of the virus. Then I noticed it was in my mothers, too.”

Padovani then looked at the plants under a microscope and saw a much lower level of trichomes than the uninfected plants, as well as much less of a smell.

Once he realized what it was, he then took samples and sent them to a lab for testing that confirmed his fears. When the results came back positive, he then quickly made the decision to just destroy all his plants and began working to clean his facility as thoroughly as possible, while also calling around to find a new supply of genetics so he can begin growing again.

“Once I did more research, I realized I was never going to get rid of it until I just torched everything. Now I’m cleaning everything in the facility and working on getting genetics from someone to start over.”

Coutts, at A&L, says the best approach to avoid bringing HLVd into their facility is making sure they buy genetics from a reputable supplier, testing everything that comes into the facility, and having working practices on site that will help prevent any infected plants that might still come through from passing anything on to other plants.

“You can pass it on with tools, by clothing. If you’re in one room and you’re brushing by the plant with your lab coat and then go into another room and touch other plants, you’ve spread it. It’s that easy. Clean your tools, use separate tools for each room, and leave enough room in your grow rooms so plants aren’t too crowded.”

He also says purchasing genetics that started as tissue culture is an important step.

“If you love the genetics that you’ve been growing, if they’ve been good to you and you love the THC content and the flower you’re producing, the only way to clean it up is tissue culture.”

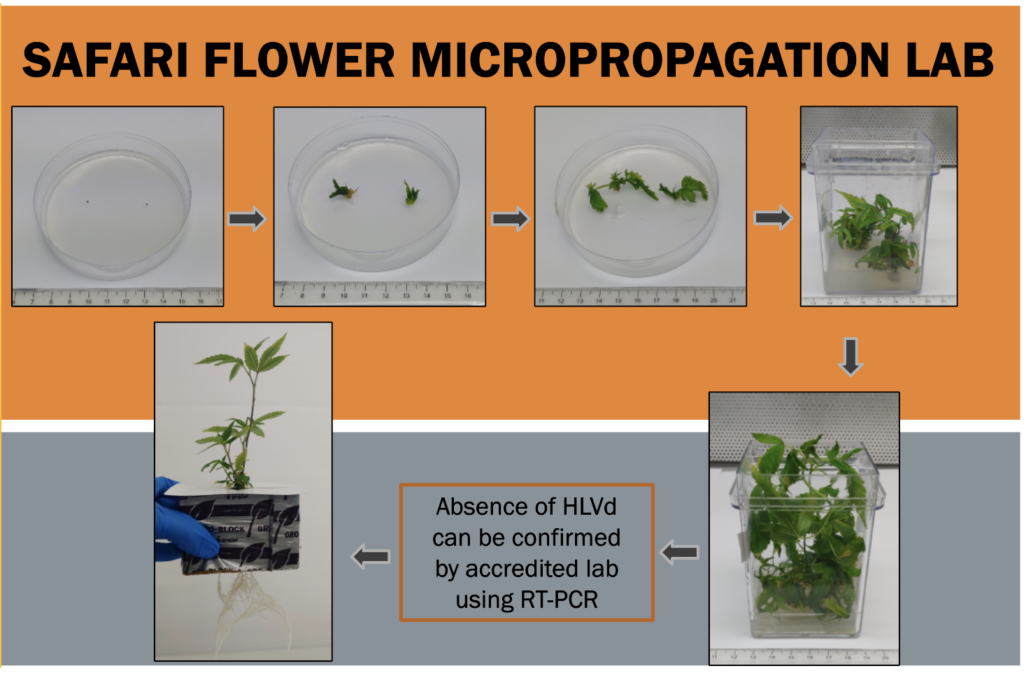

One option for saving infected genetics is through Dr. Adel Zarei, the cannabis micropropagation lab manager at Safari Flower in Ontario. Zarei has spent the last few years developing a process using tissue culture to create new, HLVd-free plants from samples from infected plants.

Dr. Zarei says he has had success with several clients who had the viroid and wanted to save certain cultivars. The process can take around nine months and requires a small sample of the regenerative material from either the apical meristem or a tip of new root.

Following detection of any infection, he says the first step is to send it to a lab to confirm the presence of the viroid. Then, if the grower wants to save any specific varieties, they should take several samples and send them to a lab like Safari, before destroying the rest of their plant material and thoroughly cleaning their facility.

Then, once the facility is ready for new plants, always ensure you’re starting with something you can guarantee is disease-free.

“The last pass to eliminate or control this viroid is starting with a clean plant. Having a certified, virus-free plant would be a good choice to start with. “

Zarei says he started looking at propagation methods that could create clean plants from samples with viroid about two years ago when reports of it emerging in Canada were just becoming known.

Leaning on his experience working with the viroid in hop plants more than a decade ago, he says he’d like to see the industry focus more on research into what varieties of cannabis may be more resistant to the hop latent viroid. He points to similar research showing that some varieties of hops are more resistant to the viroid than others, speculating something similar is likely possible with cannabis.

Cannabis breeders need to take into account the strength of the plant in general, not just THC or other cannabinoids and terpenes, explains Zarei, but also specifically looking at resistance to the hop latent viroid and other known diseases that plague commercial cannabis production.

Back at Treez Botanicals, Padovani says he hopes more producers will be more willing to be open about this disease because it’s becoming so prevalent.

“I think it’s pretty much everywhere now, but it’s just not being talked about at all,” he continues. “That’s why I’ve been very open about it. I’ve posted on my social media because I think all the big guys have it, everyone has it, but they just don’t want to say it. I believe we’ll still persevere. I’m taking aggressive action now so that it hopefully won’t affect us in the near future. I believe we’ll bounce back, but it’s not easy.”