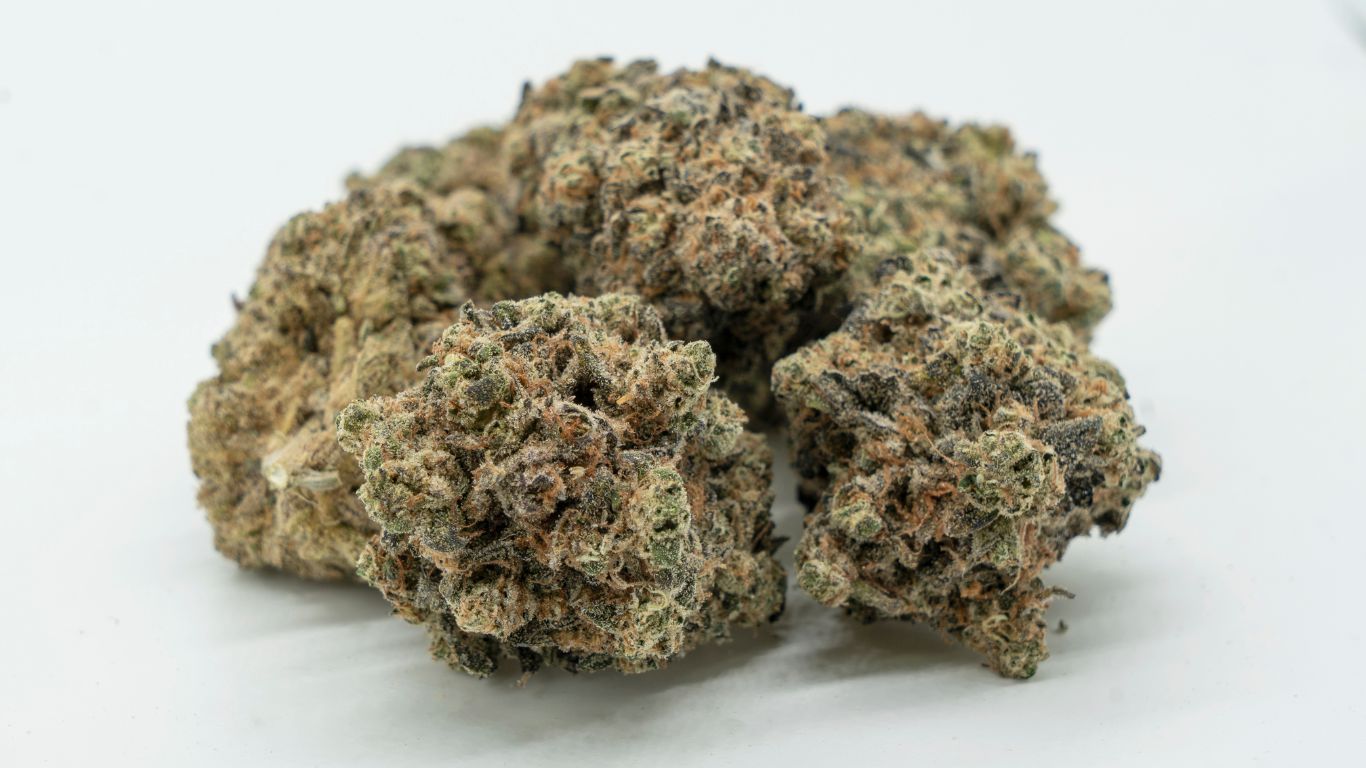

In Canada, many licensed producers have built their business models around high THC cannabis, for the simple reason that the system is skewed to reward elevated percentages. The result has been that some licensed providers may be shopping around for the labs that offer the best results.

A licensed provider will come to a lab, get a certain percentage, then shop to another lab and get another percentage.

Luther Smallwood, Pathogenia Lab

“It’s been one of the issues that labs in general run into,” says Luther Smallwood, Business Development Manager at Pathogenia Lab in Montreal. “A licensed provider will come to a lab, get a certain percentage, then shop to another lab and get another percentage.”

This practice is perhaps understandable given the market incentives that favour higher THC. There are entire brands – and stock valuations – that are dependent on cannabis testing above 25% THC.

“These labs could be using older standards or a process that delivers results with slightly more THC,” says Brian Coutts, Strategy and Business Development Manager (Food & Pharma) at A&L Laboratories in London, Ontario. “Many of them also don’t include moisture tests in their certificate of analysis, which in my view calls into question the legitimacy of their processes.”

If a sample is sent to a lab for a potency test, moisture analysis should also be performed on that same exact sample.

Tom Ulanowski, Nextleaf Labs

In Canada’s regulated market, dried cannabis is to be tested “as is”, which means it must represent what is sold to the consumer without additional processing. Labs are not supposed to report potency on a dry weight basis, which would result in higher reported THC and CBD percentages. Ideally, a Certificate of Analysis (CoA) should include the moisture content along with cannabinoid potency – but that isn’t always the case.

“There is a somewhat simple solution to the problem,” says Tom Ulanowski, a Professional Chemist (APCBC), Articling Agrologist (BCIA), and Vice President of Quality Assurance and Regulatory Affairs at Nextleaf Labs. “If a sample is sent to a lab for a potency test, moisture analysis should also be performed on that same exact sample. With this additional information, the concern that the cannabis flower was dried prior to potency testing is mitigated, unless a lab is doing something they shouldn’t be doing.”

It is uncertain as to whether over-drying of samples is an issue in Canada, given that most concerns are anecdotal, and the risk of regulatory penalties for this type of non-compliant practice is high. As well, it is questionable as to whether or not it would even make much difference.

“It’s quite simple to calculate the effect that over-drying has on potency,” says Ulanowski. “If you take a high moisture content flower, and recalculate the potency in a scenario where half the moisture content was removed, that relative change to the potency is – in my opinion – not significant enough in most cases. Improper testing methodology, or biased sampling, is a much greater concern to me.”

A call for better oversight

The cannabis industry in Canada relies on dozens of licensed labs. Some of these are older, more established businesses that also test food and agricultural products – and some labs are newer enterprises that exclusively test for cannabis.

Given the role that THC plays in the value of cannabis products throughout the supply chain, the hands-off attitude on the part of Health Canada has raised some eyebrows and brought about calls for more and better oversight, including surprise audits. Many feel that if Health Canada were to increase its oversight of cannabis labs, the overall market would stand to benefit, including those labs that are doing their best to serve their clients.

“The truth is most of the labs that I’ve spoken to and worked with are all honest, good labs here in Canada,” says Smallwood. “However, it would be good to have a blanket THC extraction procedure so that LPs can choose labs based on what really matters, which is service level, turnaround times, reliability, accuracy, and pricing.”

… as the industry is growing and maturing, we’re seeing less of an emphasis on just THC levels and more on other cannabinoids.

Heather Holmen, Alberta Gaming and Liquor Commission (AGLC)

Health Canada’s resources are stretched, yet the agency’s purview might have to expand beyond licensing labs to include additional scrutiny over sampling procedures, or perhaps conducting regular ring tests and statistical analyses of laboratory data.

“One of the major issues in our industry is that there is generally little control over sampling,” says Ulanowski. “Of course, the producers will be tempted to sample in a manner that has a bias toward the nicer looking and often more potent buds. Unless Health Canada does more due diligence on how licence holders obtain their samples, and perhaps how labs conduct their testing, and demand continues to be driven by cannabinoid content, things likely won’t improve.”

When provinces go AWOL

There is some evidence that the market is moving, albeit slowly, beyond its obsession with THC. Consumers are becoming more sophisticated, and products are increasingly being tested – and marketed – with an understanding of the role of terpenes.

“As new products are coming online, licensed producers are including more terpene profiles,” says Heather Holmen, Communications Manager at the Alberta Gaming and Liquor Commission (AGLC). “And as the industry is growing and maturing, we’re seeing less of an emphasis on just THC levels and more on other cannabinoids.”

Nonetheless, when it comes to the market’s obsession with high THC, some provinces have a tendency to wash their hands of the matter, saying that they are simply responding to consumer demand. This, despite the fact that it is difficult to find cannabis flower at under 18% THC within the regulated market.

“We choose the products we carry based on a number of factors including value, potency, price, quality, and so forth,” says Viviana Zanocco, Manager, Corporate Communications and Stakeholder Relations, BC Liquor Distribution Branch. “We work hard to offer retailers a range of products that meet the needs of their patrons. Whether consumers like high potency or low potency products is something they determine, and retailers meet their needs.”

This comment somewhat obscures the fact that with cannabis, as with alcohol, provinces play a role in consumer education, given that they are responsible for the delivery of a regulated product. Importantly, cannabis differs from alcohol in that the profit motive is driving the demand for a more powerful product.

Some provincial bodies, such as the Ontario Cannabis Store (OCS), are willing to take more of a leadership role in both serving and educating the market.

“We always encourage consumers to ‘start low, go slow’ when it comes to THC levels,” says Joanna Hui, Communications Manager at the OCS. “We are also launching a Craft Designation program to highlight products from smaller-scale production sites that employ artisanal, handcrafted processes when producing dried cannabis and pre-roll products. So, it’s not only about THC levels.”

Certainly, having the provinces take a more active role – as is the case with the OCS, which is advocating for measures that would ensure more consistency in lab testing – would improve how cannabis is marketed to the consumer in Canada, while also easing some of the pressure on LPs and labs to deliver on high THC, often to the exclusion of other product characteristics.