New Zealand’s Cannabis Legalisation and Control Bill, which will come up for a referendum vote in the country’s election on Saturday, October 17, 2020, shares many similarities to Canada’s own Cannabis Act and associated Cannabis Regulations, both in proposed intent as well as practice.

Note: The date of the vote was changed from Saturday, September 19, 2020 due to concerns related to COVID-19

While Canada was the first G7 nation to legalize, and the second country in the world to formally legalize and regulate cannabis for non medical purposes after Uruguay in 2013, New Zealand could be the third country anywhere in the world to formally regulate non medical cannabis production, sales, and consumption, pending the results of the referendum.

The referendum itself will not make cannabis legal, though, but if it receives more than 50% approval, would provide a pathway for the government to introduce a bill to parliament. If the referendum does not receive at least 50% support, the bill will not be tabled in the house.

Even if the referendum does pass – the country is currently about evenly split depending on which poll you look at – the bill itself would be expected to face considerable debate, scrutiny, and even changes through the legislative process. This process could take months, or years. Canada tabled their own legislation in April 2017 and it passed in June 2018, with extensive debate and changes in both the House and Senate.

Although the proposed legislation is written to New Zealand’s unique culture and experiences, it does share many similarities to Canada’s own legal cannabis regime, building and refining upon it in the country’s own way. Below is an exploration of some of those similarities and differences.

Protecting Public Health and Safety

Both country’s legislation presents a rationale for cannabis legalization based on the ideas of protecting public health and safety, as opposed to being a source of revenue for the public or private sector. Rather than legalizing as a form of support of cannabis or its use, both seek to legalize and strictly regulate in order to protect their citizens from the harms of cannabis, especially the youth, while ensuring those who do choose to consume cannabis can do so without relying on the illicit market.

Canada’s Cannabis Act, seeks to “protect public health and public safety” and, in particular, to protect young people by restricting their access to the product, to reduce illegal activities connected to the cannabis industry, provide access to a quality-controlled supply of cannabis, and to reduce the burden on the criminal justice system, while also raising awareness of potential harms of cannabis use.

New Zealand’s Cannabis Legalisation and Control Bill seeks to “regulate and control the cultivation, manufacture, use, and sale of cannabis in New Zealand, with the intent of reducing harms from cannabis use to individuals, families, whānau (a Māori-language word for extended family), and communities” by, among other things, deterring the illegal supply of cannabis, protecting the health of New Zealanders, especially the youth, raising public awareness of the health risks associated with cannabis use, and providing access to a legal and quality-controlled supply of cannabis for adults who choose to use cannabis.”

https://stratcann.com/how-cannabis-made-the-ballot-in-new-zealand/

Like Canada, New Zealand’s stated goal with their proposed approach is to actually seek to reduce cannabis use in the country over time. Both seek to, essentially, meet the goals that were not met under systems of prohibition in terms of protecting public health, while at the same time building a system of regulatory oversight for the adult members of their population who do choose to consume cannabis.

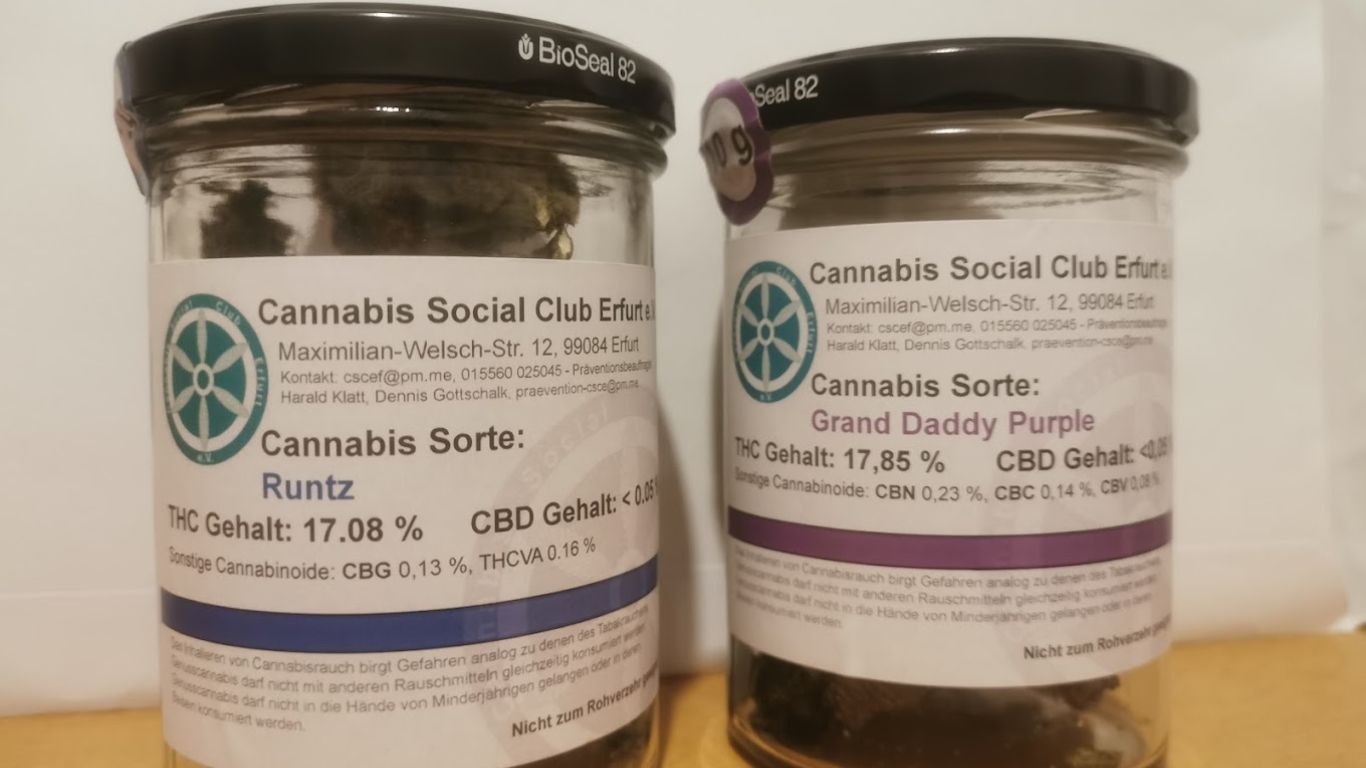

Like Canada, New Zealand proposes to establish requirements for cannabis products to meet production, testing, and labelling standards, quality controls, and restrictions on the operations of retailers and consumption premises. It also proposes an advisory committee to provide advice to the Authority on the development of the national plan.

This seems somewhat similar to Canada’s Task Force on Cannabis Legalization, although Canada’s task force was formed prior to the creation of any legislation, whereas New Zealand’s is already partially formed.

The advisory committee is to be made up of people from a range of relevant backgrounds, such as health, justice, as well as a representation of Māori interests.

Although Canada consulted extensively with first nations and indigenous communities across the country, the task force did not have any first nations members. However, it was a robust mix of representatives from across Canada, from law enforcement, public health, activism, academia, public service, and more.

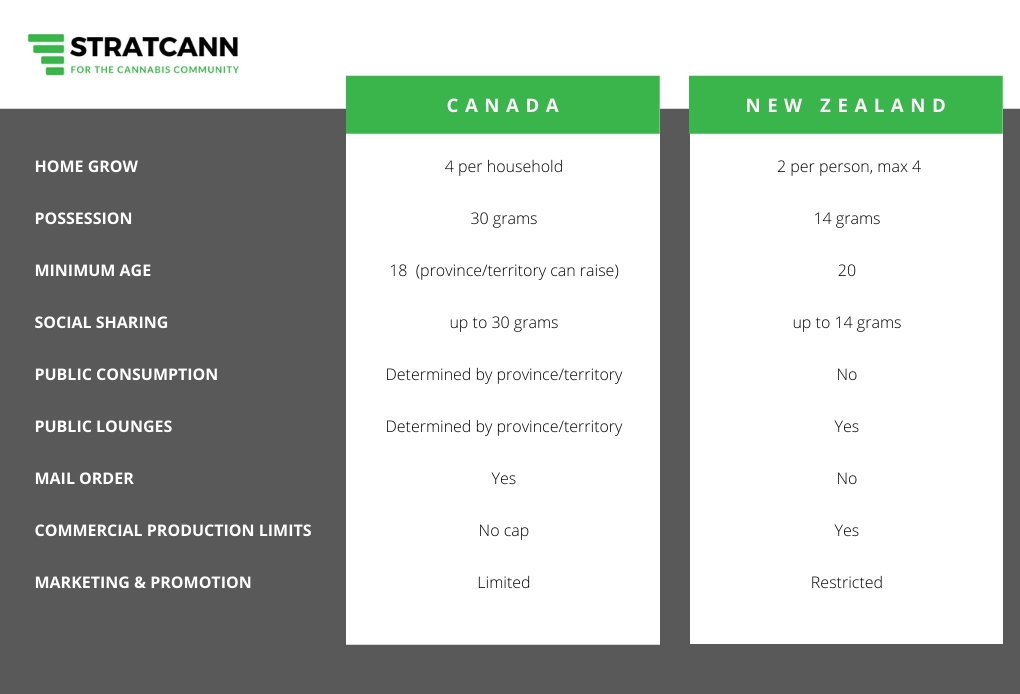

Home growing

Like Canada, New Zealand is proposing to allow up to four cannabis plants to be grown at home, although it only allows two plants per person. There would have to be at least two people living in a house in order to have four plants in one home. In Canada it is four plants per household, regardless of the amount of people who live there. Like Canada, New Zealand’s proposed legislation allows it to be inside or outside.

New Zealand proposes to allow cannabis plants in public for the purpose of transporting them. Canada’s regulations also allow this, although only when the plant is not in flower.

New Zealand seeks to only allow cannabis to be grown out of public sight and in an area that is not accessible from any public area or an area used on a communal basis. Canada has no such rule, although some provinces have made similar restrictions, such as British Columbia not allowing plants to be seen from a public place. Two provinces have outright banned home production, which is currently being challenged in court.

However, New Zealand’s rules intend to not allow any personal extraction of cannabis, although infused cannabis products are still allowed. Canada doesn’t allow non licensed individuals to use any organic solvents to produce cannabis extracts, other methods are not disallowed.

Possession

New Zealand’s legislation proposes to allow up to 14 grams in public. This also creates a 14 gram purchase limit. This is similar to Canada’s 30 gram public and purchase limit. NZ would also allow someone to have more than 14 grams if they were moving it from one location to another.

Minimum age

New Zealand’s proposed minimum age is 20. Canada’s is 18, although provinces and territories are allowed to raise this. Quebec, for example, is 21, while neighbouring Ontario is 19.

Social sharing

New Zealand would allow people to share up to 14 grams (or equivalent). Canada is up to 30.

Public Consumption and Lounges

New Zealand’s rules won’t allow public use of cannabis, but it does propose to allow consumption lounges. While Canada’s federal regulations don’t disallow either public consumption or consumption lounges, provinces and territories can set their own rules for both of these issues. Public consumption is legal in Ontario, for example, and is Quebec it is not. No province or territory has established any consumption lounges at this point.

Mail Order

New Zealand does not allow cannabis to be sent via the mail or courier, while Canada does, although there are some provincial and territorial limitations.

Production limits

New Zealand also intends to limit the amount of cannabis that can be grown under a commercial licence (market allocation), so as to not create a surplus, while Canada has no cap on the amount of cannabis that can be grown or sold or the amount of licenses issued (although some licence types have limitations on canopy size or production output). One reason Canada has given for having no cap on licenses was to not artificially inflate the value of a production licence.

New Zealand’s legislation states the purpose of market allocation is to ensure the total amount of licensed cannabis grown “will be limited to a level that is adequate for meeting current demand and will be able to be reduced over time”. It also includes language that reflects a need for a balance between prices not encouraging consumption, while also being able to compete with the existing black market.

One interesting piece of New Zealand’s proposed legislation is the inclusion of language about making decisions on how market allocation will be based using what it refers to as social equity outcomes, although what those outcomes will be is still unclear.

Potency limits

New Zealand also looks to control the potency of cannabis products, although in what ways is unclear. While Canada has no potency limits on dried cannabis flower, it does have a 10mg THC limit on any edible products.

Marketing and Promotion

Like Canada, New Zealand proposes strict limitations on marketing and promotion, in some ways more strictly than Canada. While Canada’s marketing rules are quite strict, they do still allow considerable room for companies to communicate about their products.

New Zealand’s legislation does not allow any advertisements of any kind, even behind an age gate and has more strict limits on what a label or package could display, as well as how it can be displayed in a store (in short, it can’t, even in a package). Retailers would only be allowed to display information on price. Products are not allowed to even be visible in the store except to hand them to customers or deliver them to the retailer.

It also potentially disallows any media of any kind about cannabis, even if not for the purpose of promotion. This would seem to mean that there would be no legal way to communicate anything to New Zealanders about cannabis or cannabis products of any kind, other than public health messaging. While Canada has many limits around marketing, it is not as strict, with online advertisements and social media accounts as active parts of marketing campaigns, along with media exposure and advertising in stores.

Similar to Canada, New Zealand’s regulations for labeling mirrors many tobacco regulations, with several required health warnings. Packaging must be opaque or translucent and child-resistant.

Testing

Some minimal testing requirements are outlined, about the constituents of the “smoke”, but not very specific yet. It does say that it intends to require testing for pesticide and fumigant residues, heavy metals/toxic elements, microbial contaminants, as well as THC, THCA, CBD and CBDA.

Equivalence

The only equivalence for possession that the legislation establishes is that one seed equals one gram, which is the same as Canada.

Declaration of illicit seed

New Zealand’s legislation proposes to allow a temporary process for licensed commercial growers to use “domestically available cannabis seeds” unil a legal supply is established. Similarly, Canada currently allows any new licence holder to do a one-time declaration of genetics when they are licensed, although there is no expiration on the allowance. Imports are also allowed in Canada on a very strict, limited basis.

Under Canada’s initial commercial medical cannabis regime from 2013, the MMPR, there was a similar temporary time period that allowed licensed cannabis producers to bring in genetics from licensed personal growers, which created a bottleneck for new genetics and for producers licensed after the cut-off date.