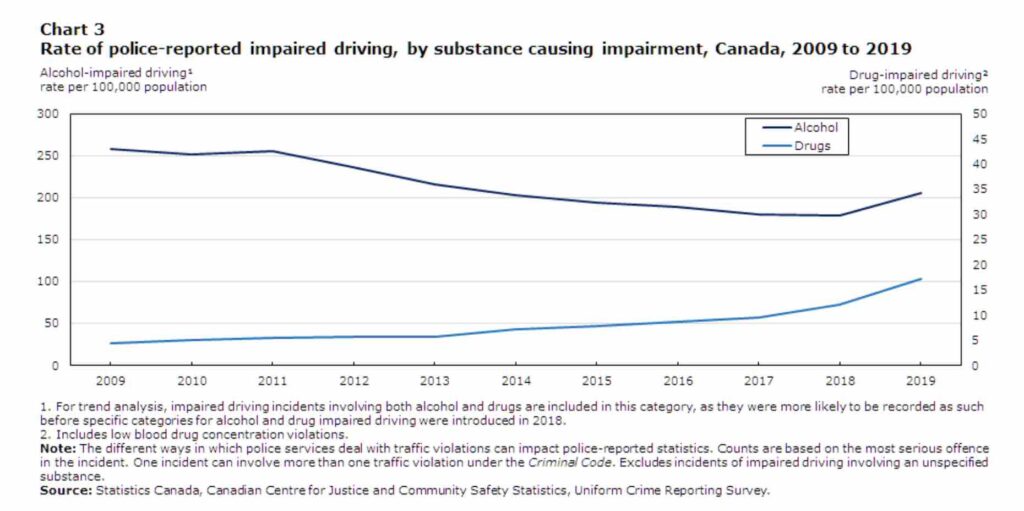

Reported instances of drug-impaired driving increased significantly in Canada in the year following legalization, but only represent about 8% of all police-reported incidents of impaired driving in 2019.

Despite these increases, instances of cannabis-impaired driving may not have risen much at all, says Statistics Canada, who released the report this week. These increases are also likely to at least partially be attributed as much to an increase in enforcement and detection as an increase in actual impaired driving, notes the report.

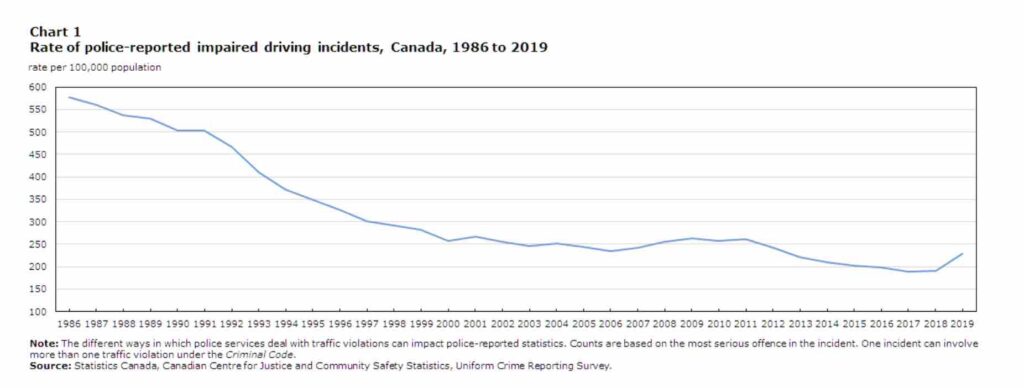

The figures show an increase in reports of impaired driving in Canada in 2019, a total of 85,673 across the country, a rate of 228 incidents per 100,000 population. This marks the end of a downward trend of such instances of impaired driving that began in 2011, but instances of impaired driving are still lower than in 2011 and more than half as prevalent as in the 1980s.

While the rate of alcohol-impaired driving incidents increased by 15%, the rate of drug-impaired driving rose 43% (6,453 instances).

Statistics Canada notes that rates of drug-impaired driving in Canada have been steadily increasing since 2008 when the federal agency started distinguishing between impaired driving as a result of alcohol or drug impairment.

Furthermore, the legalization of cannabis in late 2018 also provided police with broad new screening and enforcement powers in relation to impaired driving powers to screen for alcohol and drugs, which Statistics Canada also notes may have contributed to the rise in the rate of police-reported impaired driving in 2019.

Despite this significant increase in drug-impaired driving, the report also references data from the National Cannabis Survey showing that cannabis-impaired driving does not appear to have increased following legalization. In that study, covering the first three quarters of 2019, 13.2% of cannabis users with a driver’s licence reported driving within two hours of use at least once in the three months preceding the survey. This is slightly lower than what was observed in the pre-legalization period covering the first three quarters of 2018 (14.2%).

The same survey also showed that the proportion of Canadians who said they had been a passenger in a vehicle driven by a person who had used cannabis fell from 5.3% in the pre-legalization period to 4.2% post-legalization. Similar findings were also found in the Quebec Cannabis Survey (Institut de la statistique du Québec 2020).

The discrepancy, argues the report, is that police-reported drug-impaired driving data includes impairment by any type of drug, not only cannabis.

As an example of increased enforcement, 604 drug recognition experts (DREs) were trained in the 2018/2019 fiscal year, bringing the total number to over one thousand. In that same period, more than 8,000 police officers completed training or upgrading on the standardized field sobriety test (also known as the “physical coordination test”).

This increase in testing, says the Statistics Canada report, could mean that officers are merely uncovering those with THC in their system who had previously gone undetected, rather than simply from an increase in consumption due to legalization. This would be consistent with similar figures from Statistics Canada showing only modest increases in overall consumption of cannabis following legalization

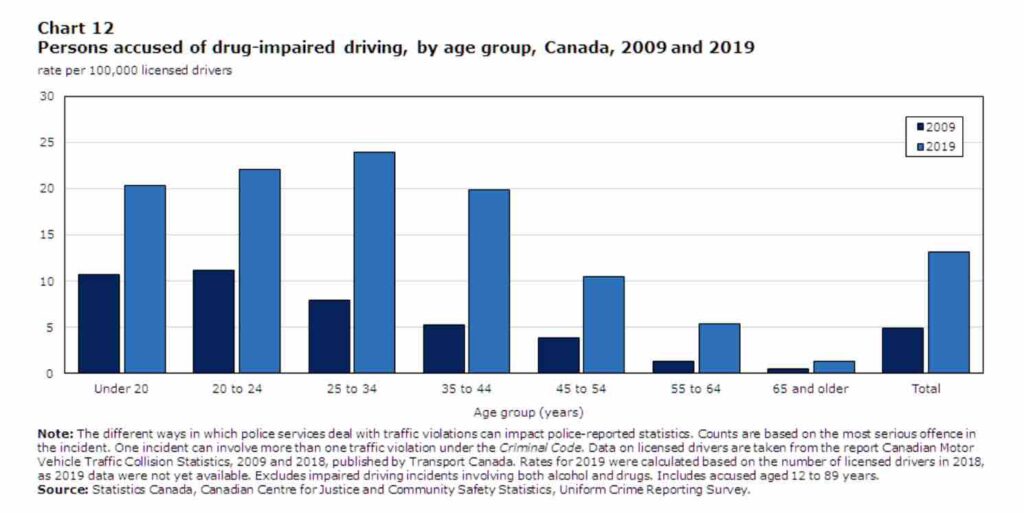

About three-quarters (77%) of drivers accused of impaired driving in 2019 were men. Young people aged 20 to 34 were also overrepresented, accounting for about one-quarter of driver’s licence holders but 44% of all impaired drivers. However, these groups had instances of alcohol-impaired driving decrease the most and drug-impaired driving increased the least.

These drug-impaired driving incidents were less likely to be cleared by charge than those for alcohol and took longer to process, but were less likely to result in a guilty finding than for alcohol.

More than half (56%) of impaired driving incidents in Canada in 2019 were “cleared by charge”, meaning police completed their investigation by laying a charge against the suspect, 10% were cleared without charge, and 33% were not cleared at all.

Those instances of drug-impaired driving were less likely than alcohol-impaired driving to be cleared by charge (49% compared with 57%) and took more than a month longer to clear than those from alcohol.

While cannabis legalization brought in new, stricter impaired driving laws and a lower blood-concentration limit for THC (at or over 2 ng (nanograms) but under 5 ng of THC per millilitre (ml) of blood for the straight summary conviction offence, at or over 5 ng of THC per ml of blood for the drug-alone hybrid offence, and at or over 2.5 ng of THC per ml of blood combined with 50 mg of alcohol per 100 ml of blood for the drugs-with-alcohol hybrid offence), drug-impaired driving incidents rarely led to charges based on these new blood concentration limits.

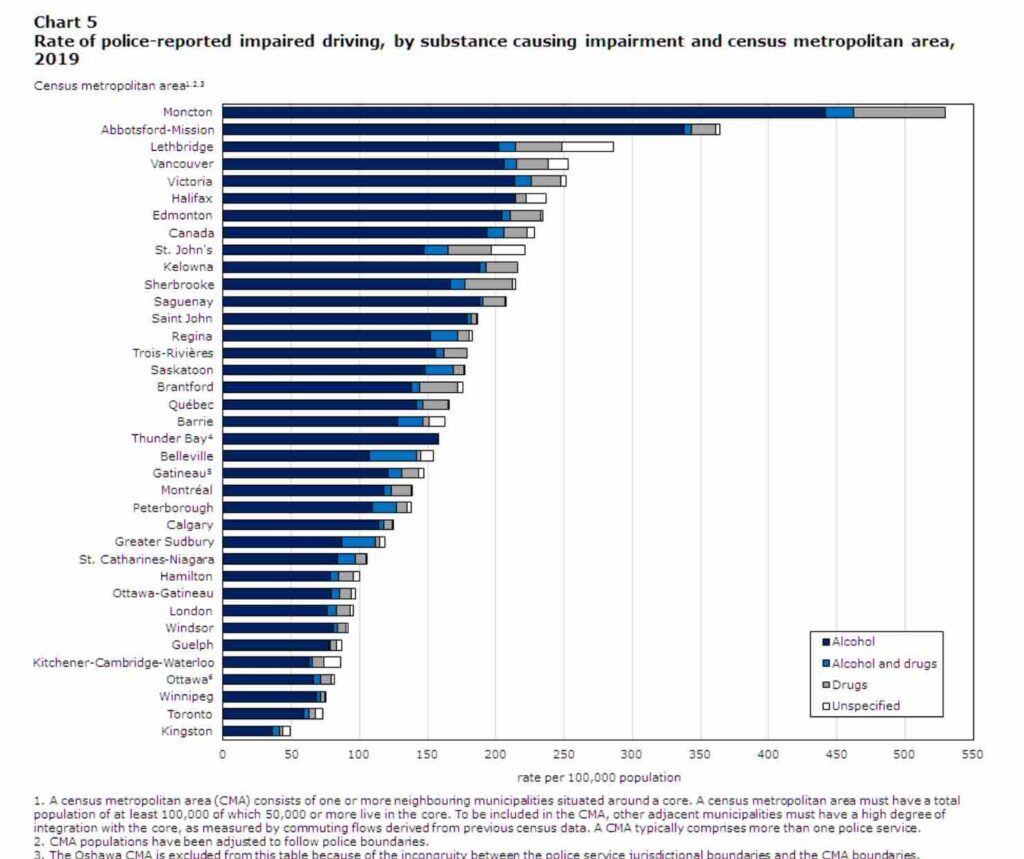

Prince Edward Island, Saskatchewan, and Newfoundland and Labrador posted the highest rates of impaired driving in 2019, while Ontario, Quebec and Manitoba had the lowest rates. Most cities had rates of impaired driving lower than the national average, but Moncton, NB Abbotsford–Mission, BC, and Lethbridge, AB saw the highest rates of impaired driving, while Kingston, ON, Toronto and Winnipeg had the lowest rates.

Despite these increases, half of the provinces recorded rates that were lower than 10 years prior. In 2019, only the Atlantic provinces and Manitoba had higher rates of impaired driving than they did in 2009.

In the territories, impaired driving rates were significantly higher than in their provincial counterparts. Nunavut, which had the lowest rate among all territories in 2019, had a rate nearly three times higher than that of Prince Edward Island. Yukon and the Northwest Territories reported rates of 2,068 and 3,139 incidents per 100,000 population.

While alcohol-impaired driving peaks on weekends and late evenings, the rate of drug-impaired driving does not vary much based on time of day.

Collecting data that can better distinguish between cannabis-impaired driving from other types, both prior to legalization as well as for several years after, will help draw a clearer picture of the impacts of cannabis legalization on the roads.