Cannabis has grown for thousands of years, adapting to different environments and cultivation practices through the ages. While legal, commercial cannabis cultivation has existed only for about a decade in Canada, human relationships with cannabis have predated legalization by centuries.

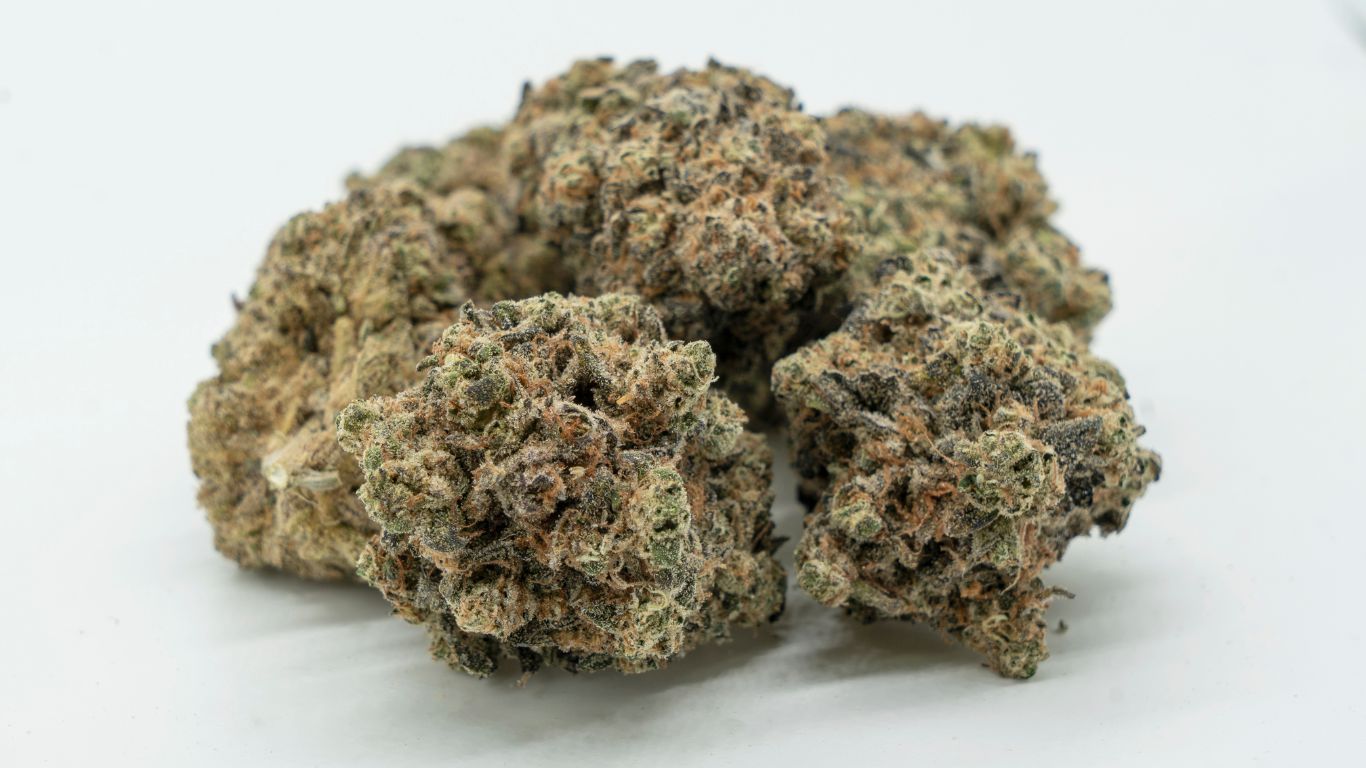

Over the years, strains have grown and developed into genetically unique plants, starting from the wild landrace cultivars, often referred to in the cannabis world as “strains,” and developing into human-cultivated hybrids produced across the country. These legacy strains have become a staple in the cannabis community, revered for their unique traits and signature cannabinoid profiles.

“Cannabis breeders throughout the world have done an amazing job creating these new and exciting strains and cultivars that are not done using conventional breeding techniques, but we produced some outstanding results, and there is always new and exciting stuff coming along,” says Collier Quinton, co-founder and cultivation director of Weathered Islands Craft Cannabis.

Mass cannabis cultivation, the hybridization of all plants, has significantly reduced the genetic stability of many legacy strains. Genetics that were once prized have slowly been diluted, and those genetics are struggling to maintain their place in the rapid production of new cannabis strains.

The question is, will the legacy strains of the past survive among the hybrids of the future?

“We don’t often have pure strains of seeds, and so we’re often doing really wild breeding where we’re crossing one plant with another and it’s not stabilized, but we often find these one-off plants. We do lose a lot of these old ones in the process. It’s the nature of the beast, really.”

Collier Quinton, Weathered Islands Craft Cannabis

History

The natural development of cannabis strains began centuries before nationwide legalization. The original strains, also known as landrace strains, are the foundation of modern cannabis breeding and the ancestors of many of the strains seen across the globe.

The term “landrace” refers to the plants that have adapted and survived in their native environments. These strains evolved over the centuries without human intervention, developing their own unique characteristics, growth patterns, flavours and aromas, and cannabinoid profiles. Some of the most notable landrace strains, such as Afghan Kush, Durban Poison, and Thai, are named after their indigenous grounds.

Since the beginning of human cannabis cultivation, landrace genetics have slowly become sparse. As the original genetics were crossbred with new strains, creating an abundance of hybrids, seeds began to disappear, and the landrace characteristics became much more challenging to track down.

“If you can find a pure landrace strain, you’re a millionaire,” says Jacob Poli, a former grower from Artiva Canada and current budtender at Flower Haze in Ottawa. “If you have the original genetics that is untainted or twisted in any way, shape or form, that’s gold in your pocket.”

Legacy strains are human-cultivated strains, developed using genetics from obtainable landrace strains and combining them to make hybrids. Some of the most notable legacy strains include Northern Lights, Skunk #1, and the OG Kush.

“I think a lot of people are leaving good weed on the table, just based off that one criteria of having high THC. There’s so much, so much more in these plants than just THC.”

Nate Miville, Big River Cannabis

Hybridization

As commercial cannabis production broke out across North America, cannabis breeding techniques and processes evolved into a new age of hybrid plants. Cross-breeding old strains with new ones created entirely new lineages.

“Cannabis is kind of unique in its breeding,” says Quinton. “We don’t often have pure strains of seeds, and so we’re often doing really wild breeding where we’re crossing one plant with another and it’s not stabilized, but we often find these one-off plants. We do lose a lot of these old ones in the process. It’s the nature of the beast, really.”

By storing seeds and cloning plants, legacy strains still have a hold on the current market. On Texada Island, B.C., Quinton incorporates preserved legacy strains such as the Texada Timewarp, Apricot Gold, and the A3 in various breeding projects. According to Quinton, older legacy strains tend to have a later finishing time than the newer strains, making them challenging to maintain.

“There’s a reason people aren’t growing the Texada Timewarp anymore, and it’s because it’s an old strain and it just doesn’t perform that well,” says Quinton. “But there are those Texada Timewarp genetics within a lot of our new strains, so in a sense the spirit and the legacy of these legacy strains is carrying on but it’s kind of in a new creation.”

In some cases, breeders will cross an existing hybrid with a parent strain to purify and enhance strain characteristics. New strains are created by combining unrelated plants with characteristics that complement each other, and those strains often go through multiple generations of breeding before they are available to consumers.

As cannabis production rates continue to climb, the pure indica or sativa strains of the past will all but disappear, their genetics carried on through a variation of hybrid plants. When strains are consistently crossed and new strains are developed annually, the genetic profiles of legacy strains are diluted.

“The more you cross-breed strains without actually un-hybridizing the original cannabinoid profile itself, sooner or later, everything’s going to be 50/50, or a blend,” says Poli. “You’re not going to have those pure indicas anymore. You’re not going to have those pure sativas anymore.”

A factor in the slow disappearance of legacy strains is the nature of the market. Since legalization, the cannabis market has grown and adapted to the new influx of consumers, new product standards, and increased demand for product traits. Nate Miville, the owner of Big River Cannabis, a retailer in Ontario, says that most people prioritize the THC percentage over the quality of the bud or the strain.

“Most customers coming through the door, unfortunately, are looking for high THC, lowest price possible,” says Miville. “There is a small set of customers that are looking for strain-specific, terpene-specific, they don’t care about THC. But those customers, they’re a niche customer. They’re not the majority.”

The demand for products with high THC has shifted the growing practices to prioritize THC percentages and flavour profiles over preserving older genetics. Legacy strains usually have a THC range between 19 and 20 percent, and due to the current demand for high-THC products, those strains are being left behind.

“I think a lot of people are leaving good weed on the table, just based off that one criteria of having high THC,” says Miville. “There’s so much, so much more in these plants than just THC.”

“I think high THC polyhybrids will continue to dominate,” says Adam Hicks, founder and head grower of Green Rose Farms. “Older legacy strains, or the ones that still remain, will continue to be used for hybrids, and some may find a way onto retail shelves on their own if they can approach the mid-20s in THC percentage. Unfortunately, I think the future is bleak for a lot of legacy strains that can’t hit 20 per cent.”

Although the pure strains of the past may one day vanish from the market, their legacy will remain in generations to come. The genetics of famed original strains such as Northern Lights and Gorilla Glue will live on in their children, a hint of the past to carry us forward into the future of cannabis genetics.

“I think, unfortunately, [legacy strains] are probably not going to fare that well. I think that’s just the nature of the business,” says Quinton. “Their legacy will carry on, but they themselves in their entirety will not.”

Content by: Kate Playfair