The Dutch government is exploring options for regulating the supply chain for its hundreds of cannabis “coffee shops,” although any possible changes to its current model are not expected for several years.

The pilot project is expected to formally begin in 2024 and will include exploring the possibility of a “closed cannabis chain” for cannabis coffee shops in several cities across the country. A report on the project’s results is expected by 2028, with a possible extension of another 18 months.

A new research paper examines the subject and can also be explored in-depth here.

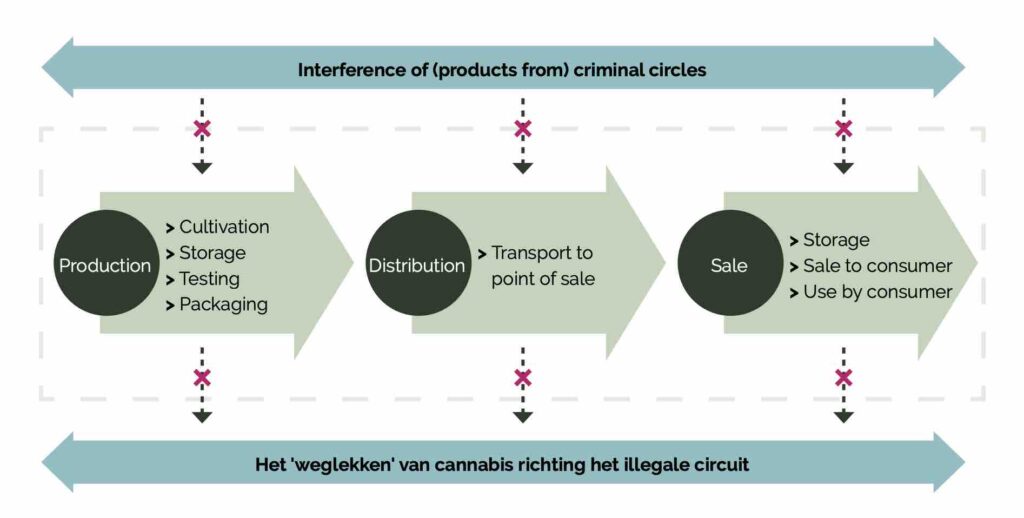

The goal of the closed-loop experiment is to unpack the possibility of a quality-controlled cannabis production and distribution system in the country as an alternative to the current “tolerance policy” that has not-legal-but-tolerated “coffee shop” style points of sale, and unregulated, illicit growers who supply them.

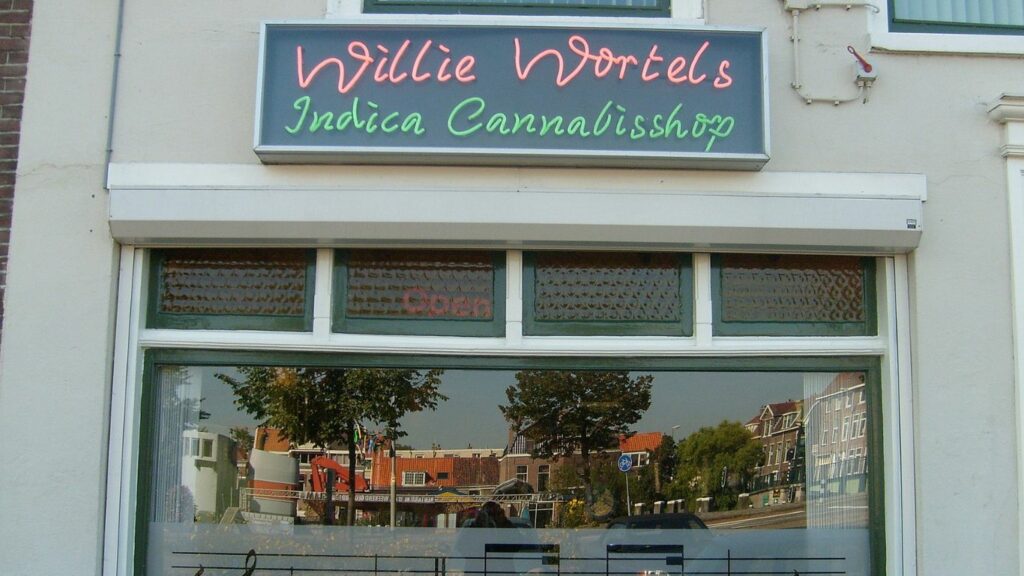

That policy, first introduced in the Netherlands in 1967, allows adults to buy small amounts of cannabis in designated “coffee shops.” However, the issue of how to properly regulate the supply of those coffee shops has long-simmered in the country, citing concerns with public safety and law enforcement, especially with many of the commercial growers located in residential areas.

Then, in 2009, an advisory committee looking into the issue recommended a small-scale experiment to explore how to regulate coffee shops’ supply. In 2015 the Association of Dutch Municipalities added to the pressure on the government to regulate these supply chains.

This led to the creation of the Coffee Shop Chain Act, which was successfully passed through parliament in 2020. Since then, the Dutch government has been preparing for the study, based on the input of its expert committee.

The committee—which consisted of experts in public health, addiction, law enforcement, local government, criminology, and law—held round table discussions with stakeholders like mayors, coffee shop owners, cannabis producers, regulators, scientists, cannabis users, and addiction experts.

The pilot project will include a “limited number of reliable and highly qualified growers” who will need to meet specific requirements, along with a limited number of authorized delivery agents from producer to retailer.

The committee recommends including numerous small and medium-sized cities across the country. Seventeen out of 23 municipalities who applied were eligible to participate.

In addition to being able to better monitor both the safety of the cannabis and its supply chains, the program will also seek to evaluate consumer purchasing habits, such as how many purchases occur within the currently “tolerated” system vs the entirely unregulated illicit market in the country.

Similar to Canada, the committee’s report also discusses the challenges of such an experiment and any possible future legalization, which is still in contradiction to existing international laws. This is one reason why Holland is not seeking to import any cannabis for this trial.

Growers selected for the program will be required to pass various microbial and pesticide testing standards, and will potentially need to adhere to Good Agricultural Practice (GAP) and Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP). The committee also recommends a “soft” approach to any recommendations for irradiation or remediation, given stakeholder feedback citing consumer distaste for such a designation.

Product labels will be required to include warnings, related information, and a THC logo, and products must be sealed in a resealable child-safe container. Selected growers will be required to be registered with the Chamber of Commerce. The committee recommends selecting around five to ten growers. Presently, ten growers have been contracted.

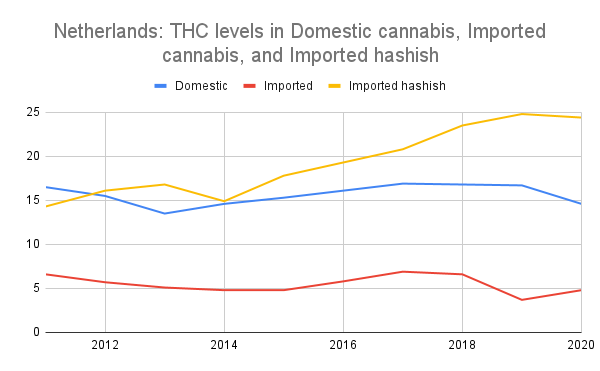

Growers will also be asked to offer a variety of THC and CBD levels. This is based on samples of cannabis from the country’s coffee shops showing cannabis sold to have an average THC content of about 17 per-cent, compared to about 6.9 per-cent THC for samples from illicit imported cannabis (primarily from Morocco, says the report).

Imported hash had an average THC content of 20.8 per-cent in the 2016/17 testing. In the report, Dutch-made hash had an average THC content of 35.1 per-cent in the same year. Of all cannabis products, only imported hash had a significant CBD content at 8.4%.

Based on this, the committee recommended fifteen cannabis varieties and ten hash varieties should be sufficient for the initial stages of the pilot project. The committee does not recommend including “space cakes” and other edible cannabis products, citing public safety concerns, especially with accidental ingestion from young people.

Although taxes cannot be collected due to international law, the committee recommends a possible surcharge on cannabis sales through the program that could feed into a national fund for the prevention of cannabis use, abuse and addiction.

Retailers (which can be “coffee shops” or other points of sale) will be required to only sell cannabis through the closed-loop program and, like the growers, be registered with the chamber of commerce. Sales will not be allowed to those under the age of 18.

While the goal of the experiment will be to explore the possibility of a regulated domestic cannabis supply chain, the committee also notes that the study may show such a program is not feasible. Such a decision will be made by the government in the future based on these results.

At the end of 2020, the Netherlands had 564 officially “tolerated” coffee shops spread over 102 municipalities. The number of cannabis coffee shops has been declining year-by year since at least 1999 when there were still 846 coffee shops.

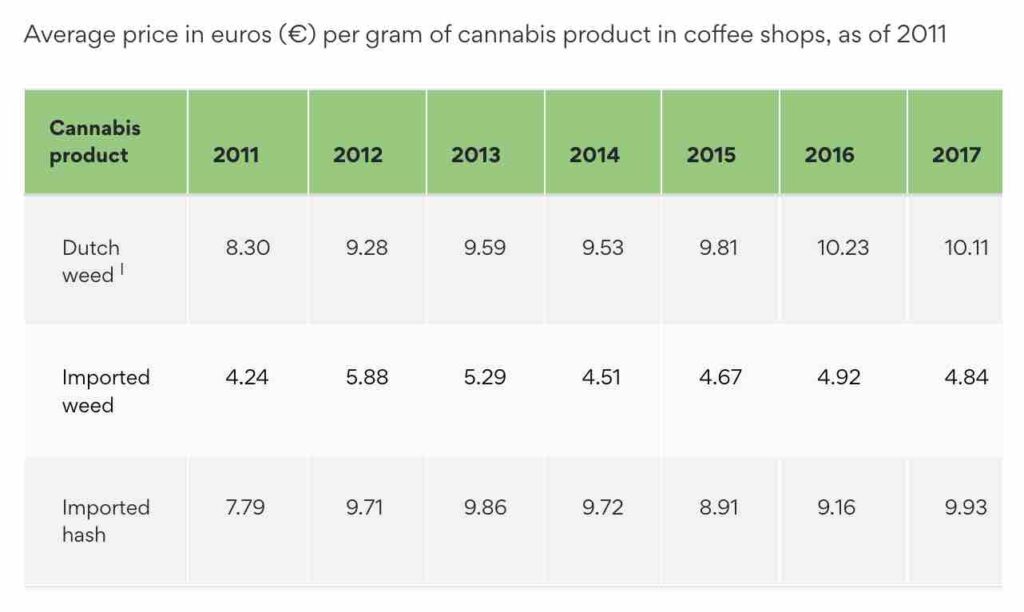

According to a 2019 survey, the average price of one gram of Dutch-grown cannabis rose from 6.20 euros in 2006 to 10.31 euros in 2018, and dropped for the first time in 2019 (9.90 euros). The price of imported hashish in the Netherlands has fluctuated since 2009. The price per gram (9.97 euros) in 2019 was comparable to that in previous years (2017 and 2018).

Feature image via Wiki Commons