Mango. Myrcene. Boosts your high. Everyone knows it. Right?

It’s scientifically proven. Ever heard of the Entourage Effect, bucko?

I don’t know who was first to alliterate Myrcene and Mangoes, but I’d like them brought to justice. The purported effects of mango and myrcene in popular cannabis culture have become so myriad and widespread that one might consider the fruit and molecule to be bioequivalent.

If you’ve spent more than three-and-a-half minutes on #terpene TikTok you’ll no doubt recognize some of these popularly claimed effects attributed to mango and myrcene (and terpenes generally, and sometimes vitamin C), including but not limited to:

- “Intensifying” the effects of THC

- Reducing THC tolerance without reducing consumption

- Increasing blood-brain-barrier permeability

- “Synergizing” with cannabinoids

- Causing sedation and analgesia (the “indica” effect)

And in the wake of mango mythology and entourage gospel grows an entire category of terpene-focused edible and supplement companies, stirring a cyclone of confirmation bias in a vacuum of evidence.

Terpenes in Mango

Are mangos truly “rich in myrcene” as every single weed education and marketing blog ever to exist suggests? Not so much.

Volatile compounds in mango are present in concentrations ranging from 18-123mg/kg (1.8 – 12.3 mg/100g) of fresh fruit—depending on the cultivar, of which there are thousands.

Monoterpenes are the most abundant volatile compounds in mango, present alongside acids, alcohols, aldehydes, ketones, lactones, and esters.

But despite popular claims, myrcene does not seem to register dominantly in mangoes. Available data indicates that 3-carene, limonene, terpinolene, and pinene, are among the dominant terpenes in most cultivars.

In one analysis of 25 mango cultivars, myrcene was detected in three and was dominant in only one, in which it accounted for 58% of total volatiles. In the other two, myrcene comprised just 0.5% and 1% of total volatiles.

An analysis of the sap of 7 Indian varieties did include myrcene alongside ocimene and limonene, while in 9 cultivars grown in Pakistan myrcene is not listed as present.

An analysis of Bowen mangos, which account for over 80% of Australia’s annual mango market, found that myrcene comprised only 1.6% of total volatiles. A similar analysis of Tommy Atkins mangos, which are the most extensively planted mango in the Americas, did not list myrcene as a detected volatile.

Taken together this suggests a fresh mango could contain 5-10mg total terpenes, of which myrcene is likely to account for fractions of a milligram.

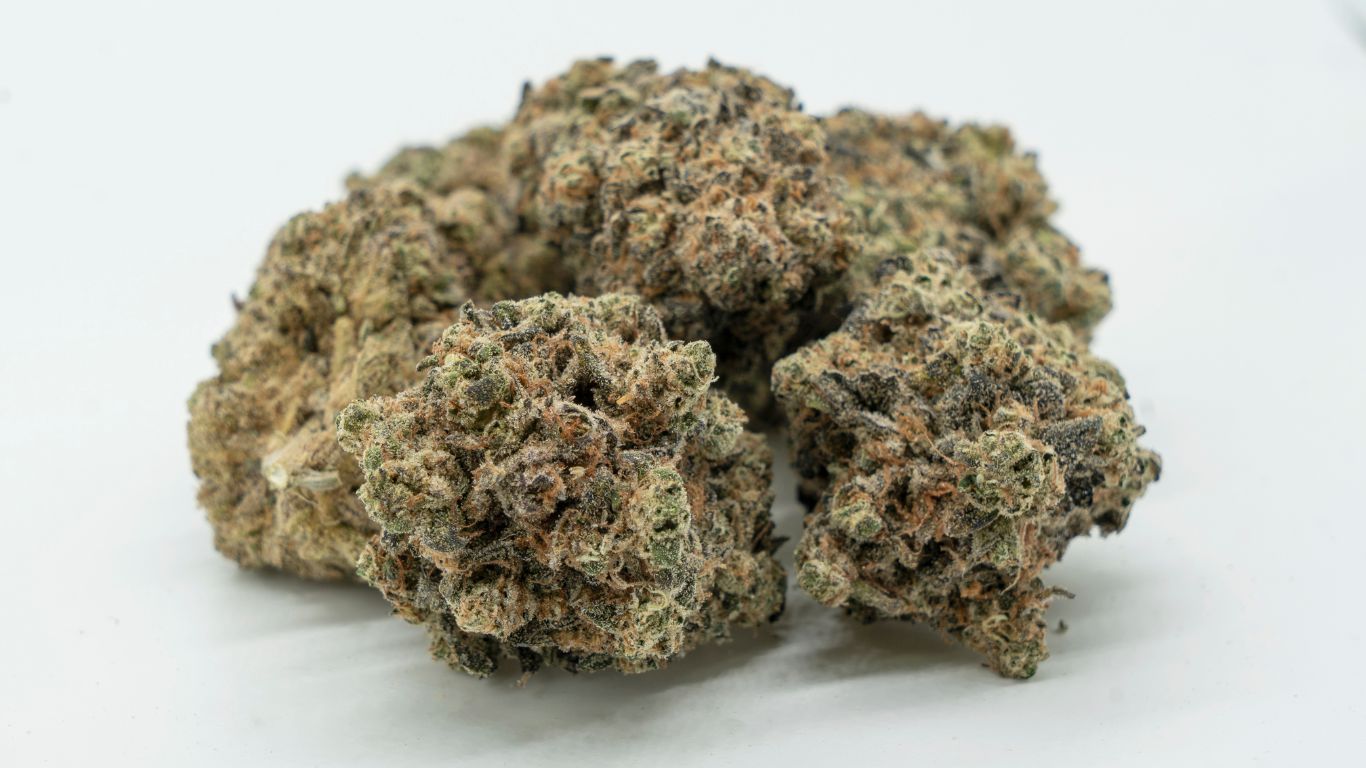

Terpenes in Cannabis

By contrast, herbal cannabis is more fragrant and contains more terpenes than fresh mangos, with myrcene being among the most dominant. Total terpene content in premium herbal cannabis can comprise up to 40 mg per gram, chief among them beta-caryophyllene, terpinolene, pinene, myrcene, and others.

Myrcene content in high-quality cannabis can range from 5-20mg per gram, and it is present in nearly all cultivars produced for medical and non-medical markets where cannabis is legal.

From 1 gram of herbal cannabis with 20% THC and 2% myrcene, we can approximate:

- 1 gram contains 200mg THC + 20 mg myrcene

- 0.5 grams contain 100 mg THC and 10mg myrcene.

- 0.1 grams contain 20 mg THC + 2mg myrcene.

Terpenes in Edibles and Supplements

“Doses” of terpenes added to edibles and supplements seem to be informed by cannabis and mango terpene concentrations. Indeed the terpenes in question are abundant in most herbs and spices.

Based on the order of ingredients on one popular brand of terpene-enhanced edibles in which terpenes are listed last after what amounts to 15 mg of cannabinoid, I surmise there are no more than 10 mg of total terpenes and likely less than 5 mg, divided by 2 gummies, further divided by “proprietary blends” which means no more than a few mg of each.

A terpene supplement company with a large social media following advertising “terpene potions for all of your emotions” (perfectly encapsulating their marketing technique) sells a “dose” of 15mg myrcene in its flagship 60 mL shot called INTENSIFY. They offer a range of four other shots, each with 15-20mg blended terpenes, bookended by a product called WAKE which contains an additional 100mg caffeine.

The shots are $42 USD for a pack of 12 (720mL) and the company employs social media to amplify positive testimonials and suppress neutral or negative ones. Skeptical claims as to their efficacy and lack of evidence are regularly met with zealous defence by adoring fans (who often receive free product in exchange for testimonials).

Plausible Bioavailability, Dubious Bioactivity

The rapid absorption and distribution of cannabinoids by inhalation would suggest the same is probably true to an extent for terpenes. Pharmacokinetic evidence also suggests this. The increased bioavailability from inhalation, combined with the generally high concentration (ie: greater than 0.5%), lends plausibility to the hypothesis that myrcene, and terpenes generally, may meaningfully contribute to the therapeutic and psychotropic effects of herbal cannabis.

The pharmacology of pinene may also lend plausibility to inhaled terpene bioavailability, and the antibacterial effects of many terpenes may even shed light on the markedly lower morbidity and carcinogenicity of cannabis smoke when compared to tobacco smoke.

But medical and psychotropic terpene effects remain largely hypothetical despite droves of recursive anecdotal narratives influenced by dogmatic interpretations of Taming THC.

Differences in individual smoking or vaporization techniques, and pyrolytic degradation and loss, also confound things (we’ll get to that).

And with reduced bioavailability comes reduced plausibility of effect. Generally speaking, when it comes to oral doses, cannabis terpenes do not seem to absorb as well into the bloodstream through the GI tract, and absorption varies substantially between terpenes.

One pharmacokinetic study in humans (n=10) looked at blood plasma concentrations from oral doses of 11.3 mg/kg a-pinene and 1.1 mg/kg myrcene. The preliminary data suggest a generous approximation of oral bioavailability at 1% and 22% for a-pinene and b-myrcene respectively, with a substantial margin of error.

In an overview of terpene pharmacokinetics, another study is mentioned wherein humans were given an enteric tablet containing several terpenes, including cineole, limonene, and pinene. Only trace amounts of cineole were detected in blood plasma and none else.

Effective Concentration and Mechanisms of Action

Once absorbed, how much terpene in blood plasma might be required to produce an effect in a human? What receptor mechanisms does it engage to produce them? No one really knows.

Generally speaking, terpenes are thought to have broad-spectrum anti-inflammatory effects; beta-caryophyllene is famously an agonist of CB2 receptors, and pinene may inhibit acetylcholinesterase, to name a few possible mechanisms of action.

But the evidence for terpene “entourage” is low-quality, as it is based almost entirely on preclinical cell culture and animal experiments employing doses much greater than found in herbal cannabis, terpene supplements, or fruit.

For instance, myrcene and other terpenes are known to improve the transdermal absorption of certain compounds, which has led to a popular myth that myrcene helps THC permeate the blood-brain-barrier, however, “perusal of claimed references in the popular literature shows a lack of hard data regarding brain transport.”

Myrcene’s sedative and muscle relaxant properties have been demonstrated in mice at 100 and 200mg per kg. Myrcene’s pain-relieving properties were demonstrated in mice given intraperitoneal and subcutaneous injections of doses ranging from 10 – 40mg per kg. This was impressively reversed by naloxone administration, leading study authors to posit that myrcene may have utility as a peripheral analgesic through an endorphin-releasing adrenoreceptor mechanism.

But herbal cannabis (1g), cannabis edibles, popular terpene supplements, and fruit, all contain generously, on average, 15 mg or less of total terpene (individual or blended), including myrcene – amounting to human doses measured in fractions of a mg per kg.

Confounding Factors

While this all sounds very exciting for wellness industry copywriters and lab mice on hot plates with deleted genes who enjoy a romp in a maze and the occasional dose of phenobarbital – no high-quality evidence exists to support popular health or psychotropic effect claims for terpenes in humans, be they from cannabis or supplements…let alone fruit.

In fact, the regularly updated and arguably best evidence compendium for herbal cannabis ever produced by a federal government health agency says “there is little, if any, pre-clinical evidence to support the ‘entourage effect’ hypothesis at all”, especially as it relates to terpenes, and no clinical trials on this subject have been carried out. This is despite gospel status in cannabis and supplement advertising.

Not only are doses of terpenes in mango so low as to be negligible, but it is also impossible to disentangle their purported effects from the very real effects of co-occurring macronutrients – like for instance: the dopamine release caused by sugar. Mangos contain a highly satiating 14 grams of sugar. Popular terpene supplements contain 7 grams and up, which in 60mL of liquid makes them sweet like soda pop.

Despite the higher relative plausibility of effect from terpenes by way of inhalation, the pharmacology of cannabis smoke remains highly dynamic and unpredictable, thanks in part to high temperatures which convert terpenes into benzene and methacrolein.

Speaking of which, the large presence of carbon monoxide, ammonia, and other hydrocarbons, in cannabis smoke and vape aerosols are also strong confounders when it comes to so-called “strain-specific effects.”

No good evidence in humans robustly supports the notion that terpenes “intensify” the effects of cannabinoids; but what’s become more “intense” with increasingly widespread legalization are placebo theatrics and CPG brand marketing, including heavily-biased influencer testimonials among other deceptive elements.

By contrast, THC is very much responsible for most, if not all, of the therapeutic and psychoactive effects elicited by the majority of cannabis produced for medical and non-medical purposes across all jurisdictions. It is, quite importantly, the most prominent pharmacologically active compound in the whole plant.

THC has biphasic effects on mood, meaning low and high doses can elicit anxiogenic or anxiolytic responses in people; effects commonly attributed to specific cultivars, terpenes, and “indica/sativa” categories.

THC and CBD also happen to cross the blood-brain barrier all by themselves.

THC has been clinically demonstrated to reduce neuropathic pain, stimulate appetite, reduce nausea, and reduce spasticity, among other potential therapeutic uses. CBD has been clinically demonstrated to reduce seizures in catastrophic pediatric epilepsies.

Such a degree of bioactivity in humans has not been established for terpenes. And unlike their cannabinoid counterparts, this dearth of clinically validated indications is not born of prohibition or drug war politik. Have you ever seen a t-shirt or placard that read “Legalize Turpentine”?

Conclusions

In pot culture the Entourage Effect is a forgone conclusion, but scientifically speaking it is an unverified rudiment of a naturalistically appealing hypothesis of cannabis polypharmacology.

Terpenes in cannabis and mangos and herbs and spices appear to be organoleptically stimulating and little else.

They are such common irritants in plants we eat that our GI tracts are adept at keeping them out of our bloodstreams – though our lungs might not be as effective, and they definitely linger long in the nose.

Indeed their ubiquity in consumer packaged goods ranging from foods to floor cleaners, and their G.R.A.S. (generally recognized as safe) status, points to a relative innocuity which may not in fact suggest a profundity of unrealized pharmacological bounty and psychotropic specificity.

This is par for the course when it comes to most vitamins, natural health products, supplements, and essential oils. You know, the mainstay of numerous multi-level-marketing schemes.

Enough with the hot air and sugar water

Terpene myopia is a case of the cannabis industry going full goop. Cannabis and terpene supplement companies feign innovation when in reality they are capitulating to placebo and pseudoscience, rebranding aromas and flavors as health supplements and medicine.

If companies want to claim their added flavours have medicinal or psychotropic properties, whether overtly or covertly, it behooves them to fund the pharmacokinetic study, clinical trials, and peer review, necessary to support the claims behind the marketing.

Patients using cannabis for medical purposes should speak to a doctor or nurse about improving the efficacy of their cannabis treatment, not essential oil salesfolk on Tik Tok. Cannabis clinics and research centers exist for precisely this purpose.

In the meantime don’t stop eating mangoes, unless you’re allergic of course.

Mangoes are a nutritious and delicious top-shelf munchie food, great for anytime anywhere. Especially while listening to The Mango Song as performed by Phish (album version – controversial subjective assertion, i know).

But also, don’t waste your money on expensive terpene supplements marketed with naturopathic exceptionalism and influencer gimmickry.

After all, your hands and feet are mangoes. You’re gonna be a genius anyway.

Sounds intense.

Adam Greenblatt is a longtime cannabis educator, content leader, and thought creator, also known as @weedpro on Tik Tok.