A recent report from Public Safety Canada explores the most recent and evolving data on drug impaired driving.

The Annual National Data Report to Inform Trends and Patterns in Drug-Impaired Driving, explores some of the early data on drug-impaired driving in Canada before and after legalization, as well as some of the limitations in gathering that data and attempts to improve upon them. The report is the result of a Federal/Provincial and Territorial (FPT) working group (WG) on Drug-Impaired Driving (DID).

As part of cannabis legalization, the Canadian government passed new legislation giving more tools and resources to law enforcement and also began working to identify how to properly track impaired driving statistics across various provincial, territorial, and municipal jurisdictions.

Although the data is still too early to draw any meaningful trends, the process of how it is being gathered is itself an interesting look at how to measure policy objectives. It also provides an interesting look at some of the challenges of gathering that data across different jurisdictions with different enforcement and research priorities.

The working group, for example, had to first establish a set of indicators for how jurisdictions were asked to collect, collate and report data around impaired driving, as well as work towards creating even more methods for future collection.

Part of the baseline for statistics on drug-impaired driving come from new rules implemented in 2008, including the Standardized Field Sobriety Tests (SFST) used at the roadside (walk and turn, one leg stand, horizontal gaze) and the Drug Recognition Evaluation conducted at the police station by a certified drug recognition expert (DRE).

This interest in gathering data to measure what, if any, changes there are in cannabis-impaired driving incidents post-legalization is not only due to legalization, but a trend over the last decade showing an increase in drug-impaired driving incidents, including cannabis-impaired driving (around 70% of cases of DID being attributed to cannabis).

Although some of the available information can come from public polling, the most accurate information available comes through law enforcement interactions with drivers. (Data comes from population surveys, roadside surveys, police-reported incidents, as well as coroners’ toxicological analyses).

As resources for enforcement increases, a wider net is cast, likely gathering much more information than in the past. Teasing out how much of any potential increase or decrease is due to an increase in actual drug-impaired driving incidents versus law enforcement simply being more likely to come across it will be a challenge for researchers.

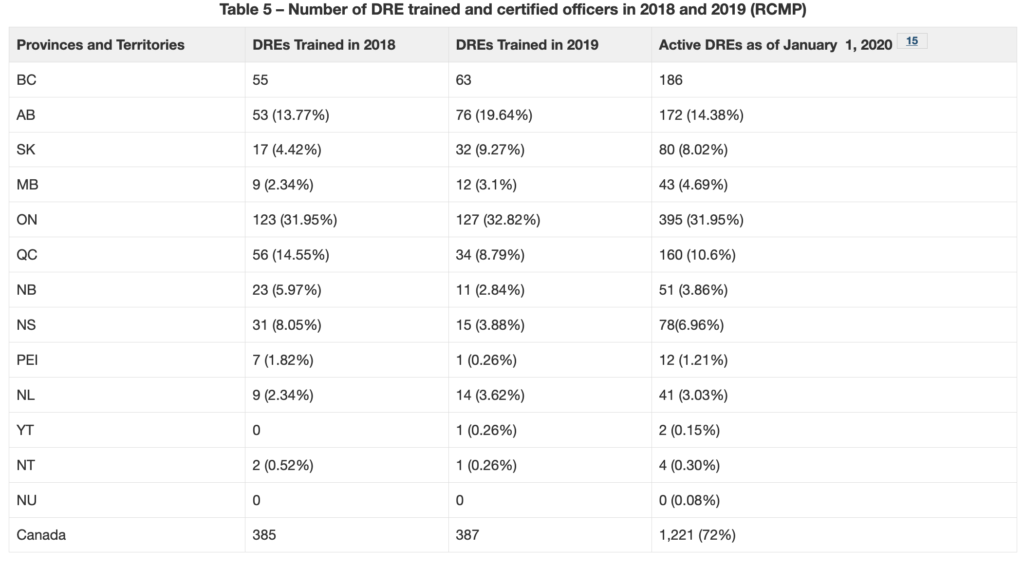

With an increase in training for law enforcement as part of the $161 million over five years that the federal government has invested in the issue of impaired driving, new Drug Recognition Experts (DRE) and Standard Field Sobriety Test (SFST) trained officers are increasingly common on roads, and new oral detection devices are available in the field that were not available a few years ago.

In 2018 there were about 13,000 SFST trained law enforcement officers and around 600 DRE’s. Currently available statistics show that there are now over 14,400 SFST trained officers and almost 1,200 DREs.

The report focuses on three broad questions: What can be said about trends and patterns in DID; what is being done to address DID; and what are the results of these actions.

Overall, the report concludes that in most jurisdictions across Canada, all data sources “tend to indicate an ongoing trend over the past 10-12 years of drug-impaired driving incidents increasing as a proportion of all impaired-driving incidents, with cannabis being the most frequently detected drug among drivers.”

It also emphasizes that this increase in police-reported drug-impaired incidents may be connected to this increase in enforcement efforts, especially given the overall trend of decreasing cannabis use over the last ten years prior to legalization.

Another issue the government sought to address with their $161m investment was public education. Although heavy cannabis users tend to still be more likely to tell pollsters they don’t consider cannabis to be impairing, overall rates of Canadians who do see it as impairing have increased.

The next Federal/Provincial and Territorial Working group report for 2020-2021 will include looking at the development of even more data collection tools on impairment.

For these numbers to truly be useful, researchers will want many more years, and the continued development of better monitoring tools will help ensure more accurate information on the subject.

Some of the data so far:

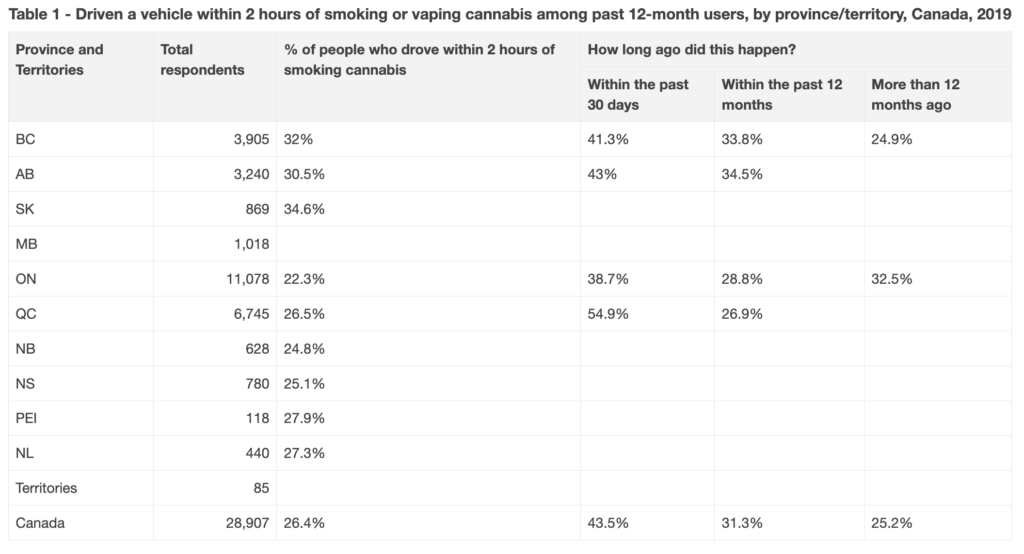

Self-reported behaviour shows about 25% of users self-reporting driving within two hours of consuming cannabis at some point in the past.

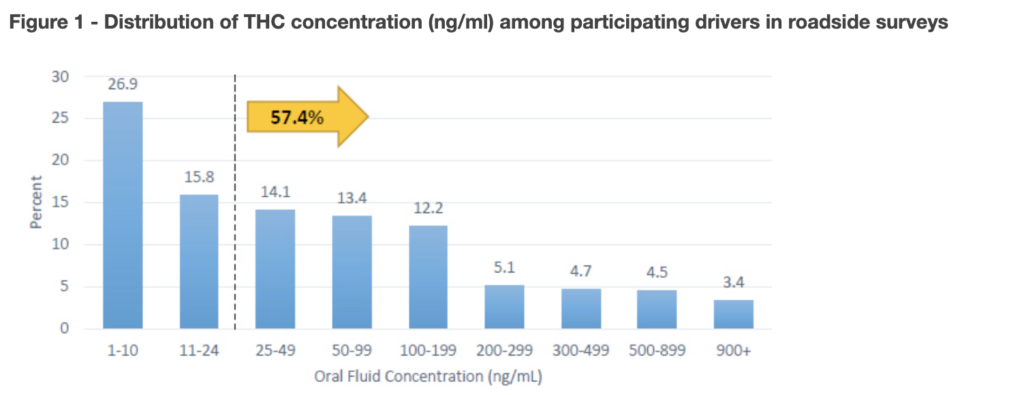

Roadside surveys (voluntary drivers) conducted prior to legalization, in BC, Manitoba, Ontario, Yukon, and Northwest Territories showed 10.2% of drivers tested positive for drugs, compared to 4.4% for alcohol. Of those drivers, 7.6% were positive for cannabis (THC), with cannabis being more common in the 16-24 age range. Over half of the THC-positive drivers had a THC concentration of at least 25ng/ml, well over the 5 ng/ml limit laid out in federal legislation.

The most recent survey in BC was conducted in spring 2018 and used a similar methodology to previous surveys from 2008, 2010 and 2012, and to Ontario’s roadside surveys.

In the survey, a total of 2,510 vehicles in 5 different municipalities were randomly sampled at night time in May and June. Of the 1,878 who consented to the survey, 13.7% of drivers tested positive for alcohol, drugs, or both, and 4.9% tested positive for alcohol and 8.5% for drugs. Among drug-positive drivers, 70% also tested positive for alcohol. The report notes that comparisons with previous surveys show that the percentage of drivers testing positive for alcohol has reduced, while those who tested positive for cannabis increased.

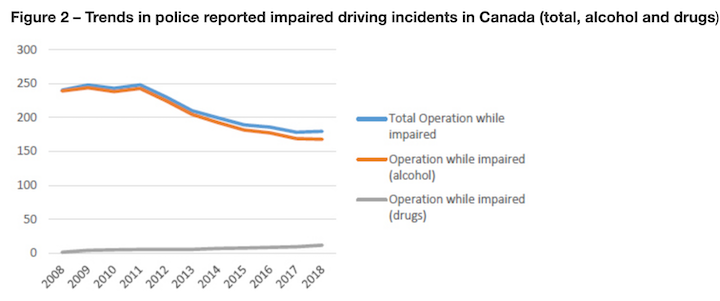

Police reported incidents: Although overall impaired driving cases have been declining from a high in 2011, and alcohol-impaired driving remains by far the most commonly detected intoxicant, drug-impaired driving cases have been increasing. There were 1,455 drug-impaired driving incidents in 2009, the first full-year when drug-impaired driving incidents were reported on their own, representing 2% of all impaired driving incidents.

By 2015 the figure was 2,786, representing 4% of all impaired driving incidents, and in 2019 there were 6,453, or 8% of all impaired driving incidents. The amount of DRE’s available as well as police use of DRE’s has doubled since 2017.

Law enforcement and others have also expressed concerns with the accuracy of some of the testing equipment used to detect THC in roadside tests.

As this data collection continues, it will help with understanding the impacts of legalization on road safety and can help guide better legislation here in Canada, and for other jurisdictions looking at developing their own cannabis legislation.