Cannabis vape pens are a relatively new and increasingly popular product on the market, but much about their health and safety remains relatively unknown due to a lack of product testing and consumer knowledge of those products.

Although these products are often perceived as not only more convenient from a consumer perspective, but safer, one expert on vape pen testing says there is much more to the story that products and consumers need to be more aware of.

Labstat International, an analytical testing lab for cannabis, has decades of experience testing similar products in the tobacco space and is now offering similar testing for the cannabis industry. In 2005, under a contract with Health Canada, Labstat became actively involved with cannabis testing by performing comparisons of the smoke produced from cannabis and tobacco cigarettes. In 2018, Labstat began offering cannabis testing services by transitioning their controlled substance license to an Analytical Testing license under the Cannabis Act.

When you’re consuming via a joint, a vapour product, or a heat-not-burn product, your deliveries are going to be dependent on a combination of parameters

Peter Joza, CTO at Labstat International

Peter Joza, the Chief Technical Officer at Labstat, says the company has created their own testing protocols for inhalable cannabis products like vape pens and pre-rolls, evolving from their work over the past several decades with similar tobacco products. He says he sees many parallels not only in the testing procedures, but in the evolution of these products and how product innovation can often move faster than the health and safety frameworks that seek to regulate them.

Evolution of product testing

“We’ve always been involved with what we call aerosol, and vapour testing. Labstat began heated product aerosol testing in the mid-90’s and vapourizer testing with electronic cigarettes in roughly 2008″, explains Joza. “Labstat came out as an offshoot from the University of Waterloo when they were testing tobacco and tobacco smoke. When we moved off campus in 1976, we were strictly doing work for Health Canada related to tobacco.”

“Our vape pen testing is a progression from the tobacco and nicotine device testing we’ve pioneered. We saw the tobacco industry progress from cigarettes or combustibles to new generation products, like heat-not-burn devices and vape pens.

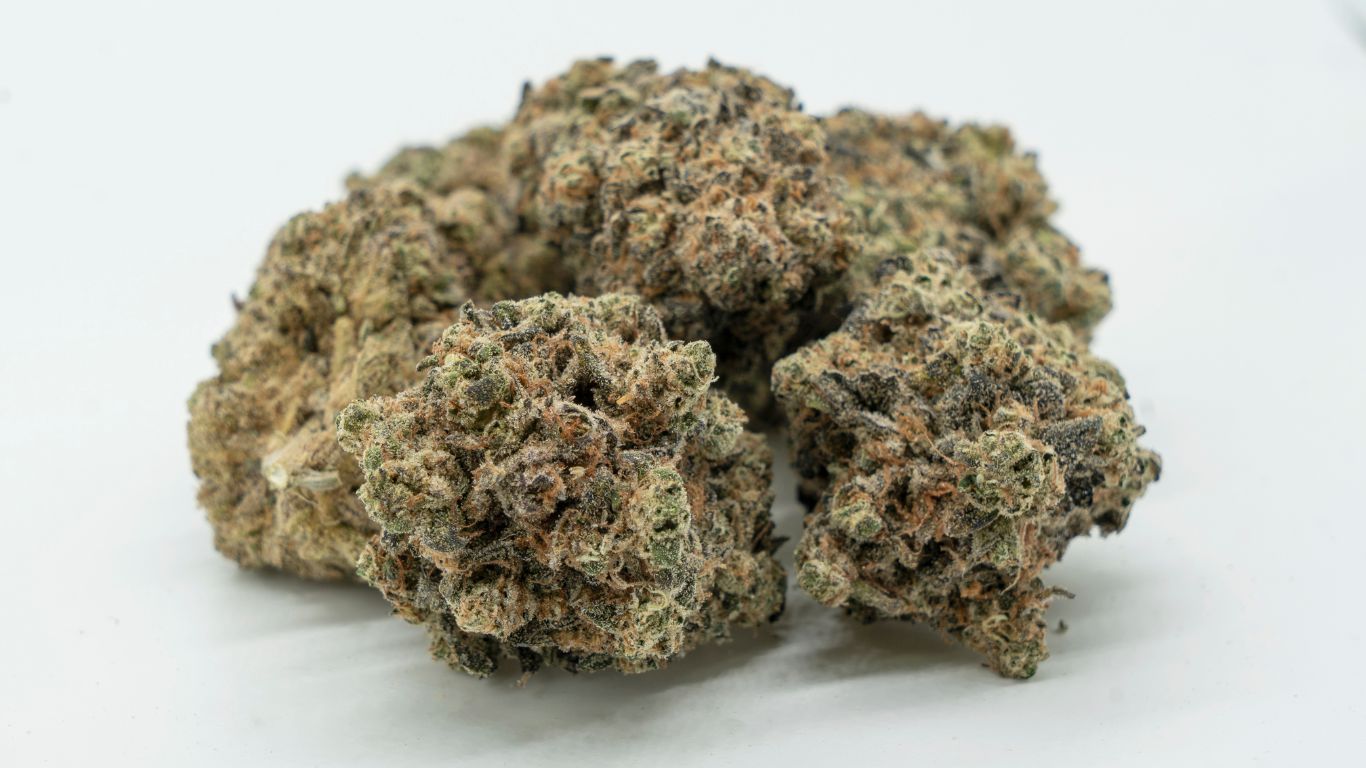

“You see the same transition happening within the cannabis space as the industry has progressed from whole flower pre-rolls to more elaborate delivery systems like vape pens. Labstat currently focuses on all modes of delivery, but Joza says the biggest demand is currently for vape pens rather than combustible products like dried flower or pre-rolls, although they do offer all processes for licenced producers to better understand and address potential safety concerns. There is some interest from a few companies looking at different filter types on pre-roll products, he says, but most of the interest from producers at this point is for extract-based vape pens.

In order to properly test these different products, Joza says Labstat looks at several variables to give an accurate overview of potential consumer consumption behaviours.

A less harmful product?

“When you’re consuming via a joint, a vapour product, or a heat-not-burn product, your deliveries are going to be dependent on a combination of parameters,” he explains. “How deep of a draw you’re taking, the puff duration, the puff frequency, along with the device itself all become factors. For example, how long is it between each puff, and how long is the puff itself? During our testing protocols, these parameters are all controlled by machines so we can generate a consistent puff volume for a consistent duration and a consistent frequency.”

Generating less compounds is likely less harmful, but I wouldn’t use the term ‘safe’.

By refining their equipment and processes, he says, and their decades of experience in the tobacco space, it helps them to look not only at what type of solution is in the vape pens themselves, but also what happens to that solution when it is heated in a vape pen and then aerosolized, before arriving at a consumers lungs.

Because most vape pens on the market don’t provide an opportunity for a standard mode of inhalation, along with accurate temperature controls, consumers are potentially inhaling unknown and unlabeled byproducts that could have negative health impacts over time.

Although he’s careful to note that vaporization is potentially less harmful than combustion, it’s important for consumers to understand that “less harmful” doesn’t necessarily mean safe.

The only driver right now is what I would call good product stewardship.

“When you burn anything; tobacco, cannabis, paper, wood, etc., it generates smoke that predominantly consists of similar by-products from the combustion and pyrolysis processes of these materials. Depending on which literature you believe, you’re generating anywhere from 4,500 to 7,600 (or more), different compounds. If you are simply heating the material, you are generating less compounds (in number and concentration) from these materials. Generating less compounds is likely less harmful, but I wouldn’t use the term ‘safe’.

Since there are currently few regulations around these kinds of testing requirements, Joza says all of Labstat’s work is producer-driven, meaning the companies who are approaching them, are taking the extra steps to identify and address potential safety concerns.”

Good product stewardship

“Right now, in the cannabis industry, there really isn’t any regulatory driver for the vapour analysis,” says Joza. “The only driver right now is what I would call good product stewardship, which comes from asking yourself: Do I know what I am selling and how it is delivering? Am I selling a consistent product?”

One of the challenges, he says, especially for smaller companies looking to compete in the vape pen market, is that product testing for cannabis vape pens can be very costly because of the nature of the product itself, unlike more common and more affordable tobacco vaping products.

“It can be a costly endeavor to take on the depth of testing we recommend for vape pens. For example, when we’re looking at say a nicotine delivery system and its a prefilled pod, those pods from a manufacturing standpoint may have a $2-$3 value on them and you’d need to test multiple pods for each independent test in order to get good, relevant statistical data because the devices themselves can still be extremely variable in their delivery.

“When you’re talking about a cannabis product, the value of the cannabis oil or liquid in that product is considerably higher. So doing, say, seven replicates across seven tests requires 49 replicates and from the inventory these producers are supplying for testing that really takes away from what’s available to be sold on the shelf. I think everyone at this point in time in the cannabis market is under pressure to generate revenue.”

With producers now using a variety of liquid formulations, it’s critical to not only test the liquid and the device separately, but to also harmonize the liquid to the device.

Product innovation moving faster than safety testing

One of the issues he’s seen that is parallel to that of similar products in the tobacco space, says Joza, is consumer perception and behaviors with these products. Although the tobacco industry has had many years to refine their vape oil formulations, cannabis companies are only just starting that process, and often trying to create new, unique formulations to distinguish themselves from the tobacco industry.

There’s the perception that as long as I’m putting in a natural extract and cutting it with other natural extracts, that it’s good because it’s all natural. That may not necessarily be true.

“There are some things that I feel are incredibly important in understanding these devices,” says Joza. “We often see a device that may have been designed for use as a nicotine delivery system and now the client is considering a very similar device design for a cannabis product. With producers now using a variety of liquid formulations, it’s critical to not only test the liquid and the device separately, but to also harmonize the liquid to the device.

“Some devices work very well with a thin or less viscous liquid, while if you put that less viscous liquid in other devices it will leak out. You need to have really good harmonization between the device and the liquid, and I think a lot of people are still trying to figure that out.

“Consumers use various types of devices differently. For example, some will take what’s called the short ‘mouth puff’ and others will take a very deep, large volume-long duration ‘lung puff’.” I think it’s really a matter of good product stewardship for the manufacturer or the licensed producer to understand who they’re marketing to. For instance, you’re not going to drink a bottle of Jack Daniels the same way you would drink a can of Bud Light. You’re going to have different concentrations of the intoxicants that are consumed differently.”

Joza, with a Bachelors of Science in Chemistry from McMaster University, says he thinks concerns with negative health implications associated with electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS) using vegetable glycerin (VG) and propylene glycol (PG), have moved people to select more “natural” products like terpenes in their cannabis vaporizer This can potentially give consumers a false sense of ‘safety’ and lead to producers experimenting with new ingredients that have little product testing when it comes to use for inhalation.

“There’s the perception that as long as I’m putting in a natural extract and cutting it with other natural extracts, that it’s good because it’s all natural.

“That may not necessarily be true. It’s a matter of whether the liquid is harmonized or working well with the device that is producing the vapour. If you’re overheating some of these extracts , there’s the concern that other potentially harmful compounds or by-products are being generated. So producers are actively considering different carriers for carrying the cannabinoids through the aerosol. In the nicotine world they focus primarily on using vegetable glycerin and propylene glycol. Their devices are a little more mature in being able to handle a relatively consistent matrix.”

“I think the cannabis world really tries to differentiate itself from the nicoine world by avoiding the use of vegetable glycerin and propylene glycol, so many of the producers are looking for new options.”

He says this process is in part what led to some black market vape pens last year, primarily in the US, utilizing things like Vitamin E acetate as a vehicle oil or thinning agent as they tried to get away from vegetable glycerine and propylene glycol and the reputation for having negative health effects. Increasingly, he says, some manufactures are using added terpenes to serve this same purpose which consumers may see as a safe alternative since terpenes naturally occur in cannabis, although in much smaller concentrations.

“I’ve been in the lab business for at least thirty years now, and things are changing faster and faster. What seems to have taken forty years for regulation to creep into the tobacco industry, I see happening at a much steeper rate of change in the cannabis industry.”

Ultimately, until there are regulations in place to require testing these kinds of products, Joza says it’s up to product manufacturers to take it upon themselves to address safety concerns for their consumers.

There will be some variation between the vapour you inhale in the first five puffs of using the device and the vapour you inhale during than the last five puffs of the devices. Especially if the device is designed to last you 100 puffs.

“There are two specific trains of thought that people are looking at. From one angle you can consider the vapour testing as an important part of good product stewardship. If you’re going to claim to have a gold standard product you must ensure that product is consistent. Meaning, if a consumer buys that product in March and goes back in April for more, they are ensured to get the same experience every time. That’s good product stewardship. The other consideration is whether or not the product is delivering what it’s supposed to deliver and not delivering what we don’t want it to deliver.”

Product standardization

“In the nicotine world they have gravitated to a few standard products and approaches, like PG and VG, so it’s easier to standardize how it works in various devices. With cannabis you’ve got a lot of unknowns. Especially if your liquid does not harmonize with your device, and you increase the probability of the atomizer itself overheating and creating undesirable compounds.

“When we’re talking about vaporizing, the aerosol that is generated from the vaporizer should simply be a distillate of the liquid that is in the pen. That’s the ideal world. In reality, that is not always the case.

“Your primary constituents coming through the vapour may be just a distillate. However, the more complex your liquid solution is the compounds you’ll have distilling, breaking down and sometimes concentrating at different rates.. In some cases, you may have compounds that because they are so heavy, they will concentrate themselves in the liquid and not even get transferred into the vapour. So you’re not necessarily even getting what you want from them, and maybe even getting some things that you don’t want.”

“What we’ve seen with the nicotine industry is that they’ve tried to simplify their solutions as much as possible so they have a better understanding of what’s distilling into the vapour. I think in the cannabis world right now the solutions are potentially much more complex..

“You’ve got so many different cannabinoids and terpenes in these formulations, some in higher concentrations than others, it’s a very complex mixture. There will be some variation between the vapour you inhale in the first five puffs of using the device and the vapour you inhale during than the last five puffs of the devices. Especially if the device is designed to last you 100 puffs.”