As Australia’s domestic medical cannabis market evolves, some companies are becoming frustrated with the country’s ongoing reliance on cannabis imports from Canada.

Still, others say demand is being driven by consumer preference.

Australia legalized medical cannabis in 2016, and by 2017, Canadian cannabis companies were announcing exports of cannabis oil and flower to the country. Although many of these initial shipments were relatively small (just the equivalent of 200 grams in 2017), by 2021, Canadian companies exported nearly 5,800 kg of cannabis; by 2023, that figure was over 34,000 kg.

The early reliance on imports came at a time when Australia’s domestic industry was in its infancy. But in late 2024, some of these companies recently told the country’s Sydney Morning Herald that they are struggling to compete with what some characterize as product “dumping”.

These accusations mirror similar ones levied by the Israeli government earlier this year to the dismay of Global Affairs Canada.

Some cannabis companies in Australia say that much of the cannabis being imported from Canada is of lower quality and that the products have fewer checks on quality than what is produced by Australian companies.

“I have no issue with imports coming here; the issue is that because they have surplus product, they’re dumping it here, which makes things difficult for local cultivators,” Nan-Maree Schoerie, managing director of ECS Botanics, tells the Herald. ECS is an Australian cultivator and manufacturer of medicinal cannabis.

StratCann also spoke with Schoerie about the issue. She explained that while some of the Canadian cannabis products coming into Australia are good quality, she thinks some companies are unloading lower-quality products from their vaults due to an oversupply in Canada.

“We have a product that comes into Australia from Canada that is extraordinarily good quality, probably for the extra years of experience,” she tells StratCann. “But there’s also an enormous amount of product that we believe is coming from stockpiling in Canada.

“That product is flooding into Australia. It’s not necessarily fresh, it’s not necessarily great, but they can sell it at a very low price.”

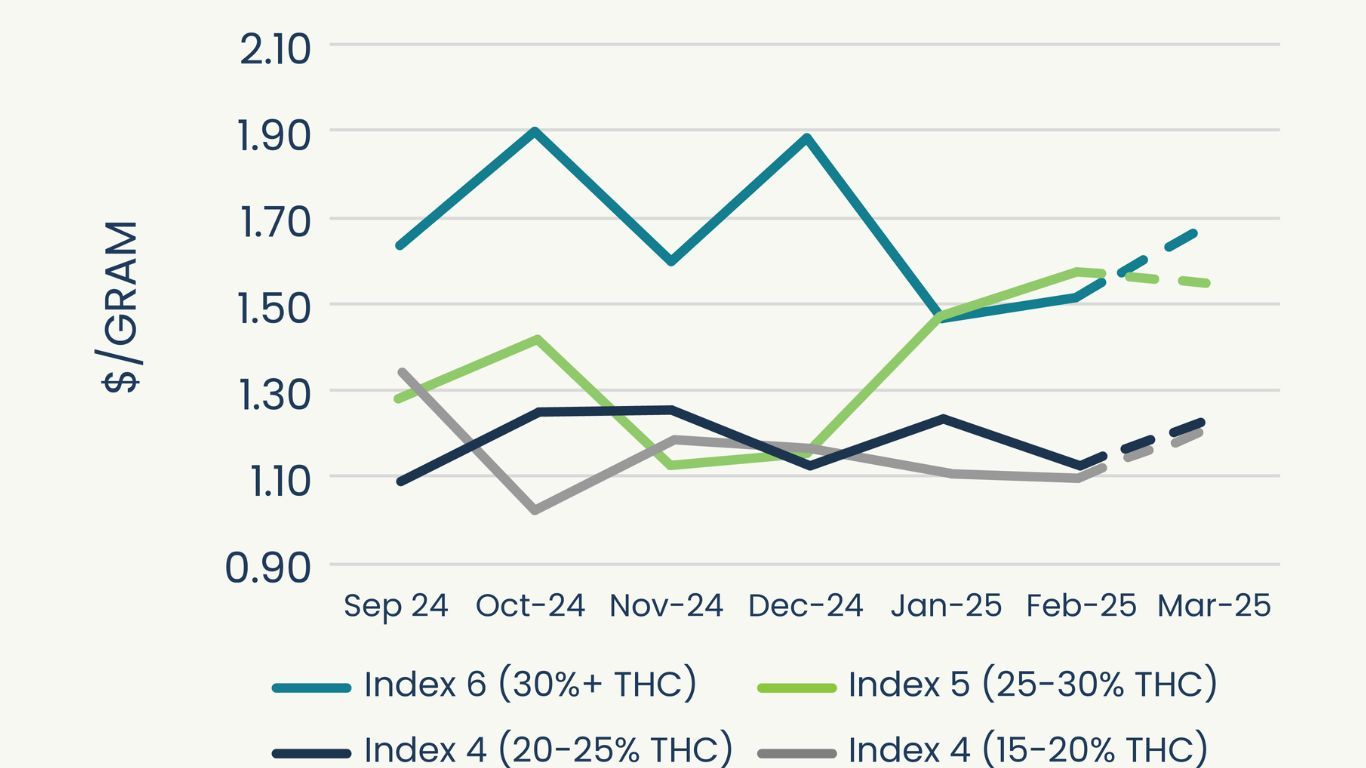

The export market is a good opportunity for Canadian companies to offload lower-quality product, but she notes this pushes the price down in Australia just as it has in Canada. While growers in Australia could get around AU$6 a gram, wholesale, in 2023, Schoerie says in 2024 that has dropped to around $4-4.50.

“That is a direct consequence of the amount of product that has come in, primarily from Canada.”

Schoerie notes that her own company exports products, as well, and doesn’t blame Canadian companies, or any others for finding markets for their products where they can.

Ultimately, she says the issue is one created by the Australian government, specifically the agency that oversees Australia’s cannabis for medical purposes program, the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA).

She explains this because the TGA, which requires Australian companies to have GMP compliance, allows companies importing their products into Australia to use a “loophole” to have them packaged in a GMP-compliant facility. She also says the TGA doesn’t have the resources to ensure the facilities that package goods in Canada adhere to Australian requirements.

Andrew Dowling, the director at an Australian cannabis wholesaler called Phytoca that focuses primarily on imports, pushes back against this argument, saying that being processed in a GMP facility in Canada or Australia is still the same standard.

“The actual growing of cannabis is not covered under GMP, anywhere in the world, because it’s not a manufacturing activity,” argues Dowlin. “It’s cultivation.”

The issue of product “dumping”, he says, is one being pushed by companies who simply aren’t meeting the international market’s demands, both in terms of price, but also in terms of quality.

“If these governments really had a problem with Canadian imports, there are levers at their disposal that they could be pulling on to turn it off.”

“It’s wrong to claim it’s being dumped. That product is being ordered because there’s a commercial opportunity and the demand is driven by the price point that is unmatched by Australian companies. If Australian companies could find a solution to that, they’d be doing it.”

Deepak Anand, an industry consultant in Canada who assists cannabis companies with exports into countries like Australia, echoes these sentiments.

“Whether it be Germany, Australia, or Israel, Canadian products are of a better quality than domestic supply. This is a reflection of what the market wants rather than this alleged dumping, which hasn’t been proven anywhere.

“I think this notion of dumping, which was started by the Israelis—it’s catchy and sounds like something nefarious is going on—but the fact of the matter is Canadian products are just of a higher quality so that’s why there’s a demand for it.”

Canadian cannabis companies have indeed been dealing with domestic price compression from an excess of supply that has led many companies to lean into the export market. Exports are seen as an easier and, at times, more lucrative path to market than selling domestically, since exports are often bulk sales and are not subject to Canada’s federal excise tax of $1 per gram.

The oversupply of cannabis in Canada that has pushed many companies to the export market has, in the past year or so, also had the effect of relieving some of that downward pressure on domestic prices. While exports don’t appear to be slowing down, it’s possible that the international market will begin to find some balance.