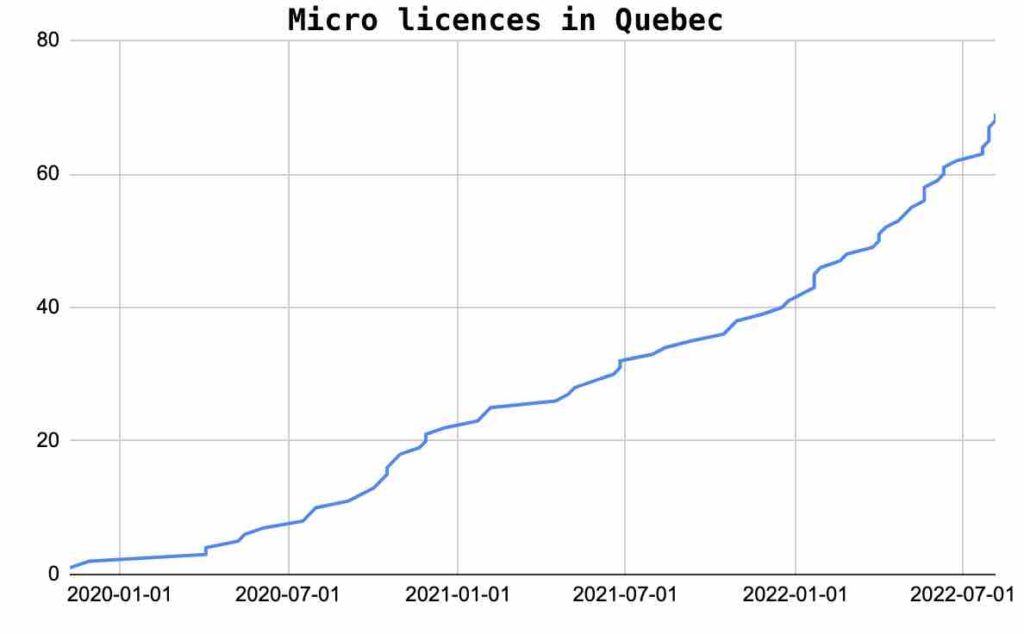

Quebec has seen a big uptick in new micro licences in 2022, more than any other province so far this year.

La Belle Province has had 30 new micro licences issued so far this year, for a total of 70. Seven of those licences came within the last month, alone. Seven of the last eight licences issued as of August 12 were in Quebec.

This compares to 14 issued this year to Ontario, nine in BC, 11 in Alberta, five in Saskatchewan, two in Manitoba, and one each in New Brunswick and Nova Scotia.

Although Quebec was behind most other provinces when it came to federal production licences in the first few years of legalization, Pierre Leclerc, the CEO of the Association québécoise de l’industrie du cannabis (AQIC), says he thinks the recent increase may be a reflection of the maturing market. Quebecers may also be more interested in the small business approach that leads many to a micro licence.

“I think Quebec entrepreneurs sat back a little and watched how the market would play out,” says Leclerc. “What we’ve seen with the big public companies so far they’re not quite profitable, so I guess… going with a smaller scale business is something that is more cultural or historical in Quebec. So building a business model around the micro licence production is something that makes sense in Quebec”

AQIC has around 75 members at the moment, including about a dozen micros, says Leclerc.

Despite the uptick in new micro licences, though, he estimates that of the 71 micros in the province at the moment, only about 30 are actively producing and selling into different markets.

One factor that he would like to see change is for the SQDC to provide more assistance to local micros who are seeking to sell their cannabis in Quebec, something AQIC has been working with the SQDC on this year.

Louis Sirois, President of Laboratoire InoVert, a standard processor in Quebec, and the President of Groupe Conseils Sirois, attributes part of the increase to a possible shift in Quebecers’ attitudes towards cannabis and their faith in the viability of the industry, especially the micro licence category.

“It could be a lot of things. It’s now cheaper to build, they understand the SOPs, and there is more social acceptability. The cannabis market (in Quebec) is still very close in the minds of people to organized crime, so we definitely do not have the same cannabis culture that people on the west coast may have. So there’s still a lot of education we need to do.”

He also says he’s seeing the SQDC pushing for more Quebec-grown cannabis products, which could be encouraging to people looking to get licenced. But in the meantime, he says his own company, Laboratoire InoVert, is still looking to provinces like BC for quality genetics and know-how.

It’s slowly going in a good direction, but there is still a need for more education.

“(The SQDC) really wants to encourage it, I think. They are pushing hard to have made in Quebec products. For now, unfortunately, I think we don’t have the best quality that you may find in the west. But they would like to put more into the market. So maybe this could encourage small growers in Quebec.”

“I don’t think there’s one reason, but it could be a combination of many factors that will bring those companies in. But we are still far behind the rest of Canada. So we are still looking west.”

Leclerc, from AQIC, echoes Sirois’s comments about a softening attitude in Quebec society towards cannabis also helping to encourage more people to look at getting licensed—even if there’s still a long way to go.

“We hope someday cannabis products will be a little bit like alcoholic products and we can work on smaller scale production, local craft-type of high-quality products for the community,” says Leclerc.

“We’re not there yet, but I believe it’s a good sign in the sense that if there’s a lot of micros and private investors, that means that legalization is probably working at transferring the market from illegal activities to the licit market, and that’s a good thing. And I think within a few years it’s going to be a good thing for (consumers) as well.”

Despite the optimism, both Sirois and Leclerc say they have seen a high failure rate for licence holders large and small in the province—a trend that extends to the rest of Canada. Both estimate that only around 30 of the current micros have commercial production in the province, a sign of both the relative ease of which getting micro licences can be compared to standard licences, as well as the challenges at then producing quality products that can succeed in a provincial market.

It is still very hard,” says Sirois. “Many of them are going out of business, big and small. There is a lack of money because no banks will finance projects here in Quebec, and there is a lack of good quality genetics, so we have… a long way to go. But it is promising.”

Featured image from mindiCANNA, a micro cultivator and micro processor in Quebec