Canada isn’t the only legal cannabis market dealing with an incentive for growers to pass the 20% THC threshold. A recent US study of two cannabis-legal states shows an “unusual spike” in the occurrence of dried cannabis products listed as having just over 20% THC.

The report, published in the Journal of Cannabis Research, suggests an economic incentive to produce lab results that show products as having at least 20% THC and suggests the need for better regulatory oversight of this aspect of the industry.

Researchers took the laboratory data from thousands of cannabis products in Nevada and Washington (55,523 and 142,847 samples, respectively) and analyzed the results looking for an “unusually high frequency” of products containing just above the 20% THC threshold.

What the results show, argues the report, is that not only are there examples of this kind of “bunching” of results just over 20%, but they only existed in the results from some laboratories represented in the samples given. That is, only some labs were reporting levels in this way. Because of this, they rule out the likelihood that growers are manipulating their samples to get more favourable THC results.

We really don’t know if these numbers mean anything. So it’s also really important for public health analysts to recognize that when you’re looking at reported THC data, there’s a ton of noise baked in.

Michael Zoorob, author of the report

The results from both states show evidence of “bunching” around the 20% THC level, “with the frequency of products reporting just above 20% THC sharply exceeding the frequency of products reporting just below 20% THC”.

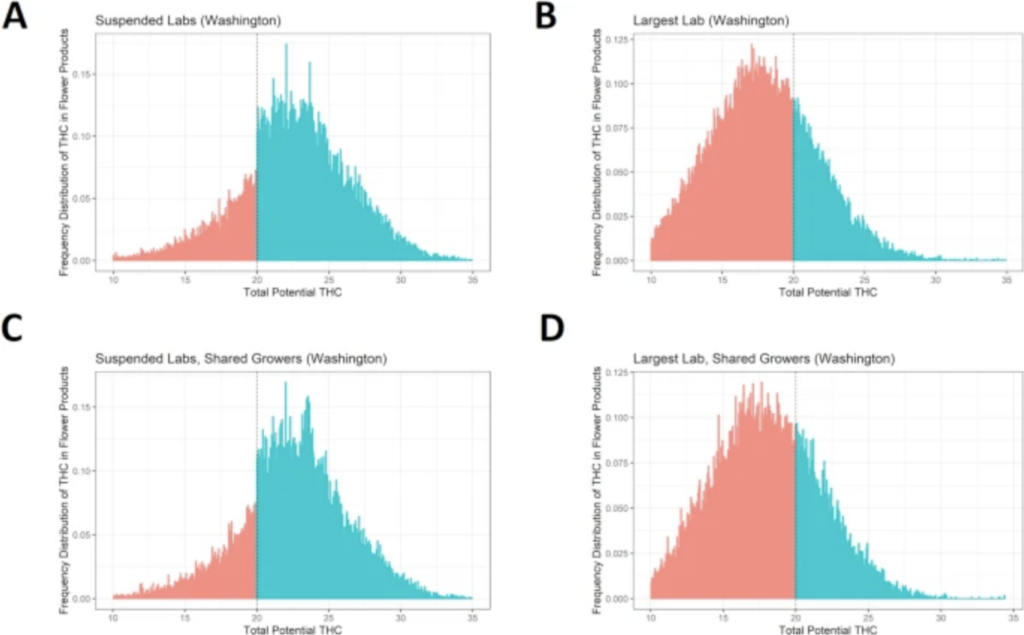

Analyses were performed using results from all labs in each state, as well as the highest volume lab in Washington, and two labs in Washington that had their licenses suspended for testing irregularities during the study period. Michael Zoorob, the author of the report and a PhD student in Government at the Harvard Kennedy School’s Malcolm Wiener Center for Social Policy explains:

“The average THC results were higher for the labs who had their licenses suspended,” says Zoorob. “But also, there’s just not the same bunching around 20% for the largest (more trustworthy) labs. Instead it’s just very smooth, which is what you would expect biologically. The plant doesn’t care if it’s got 19.8% or 20.2% THC, but consumers seem to care and you see that in the testing results for the labs who had their licenses suspended, but not for (the other labs).”

Because products in Washington note the lab that provided the testing, researchers were able to analyze results from these two labs and weigh them against results from other labs that had tested the same products. While Washington’s highest volume testing lab showed a frequency of products just over the 20% threshold only 1% of the time, the two suspended labs showed results just after the same threshold 47% of the time.

Zoorob co-authored a previous research paper looking at similar testing results in Washington, comparing the same product, from the same producer, harvested at the same time, with results from different labs. Despite all these similarities, he says what they say was a deviation of, on average, about 5 percentage points.

His main concern, he explains, is to help other researchers understand that the published THC numbers are often not accurate. So anyone using that data in whatever kind of research they are doing needs to take that into account.

“We really don’t know if these numbers mean anything,” says Zoorob. “So it’s also really important for public health analysts to recognize that when you’re looking at reported THC data, there’s a ton of noise baked in.”

He says he thinks it’s growing pains for a new industry, especially one with little formal oversight given the patchwork of state laws and brand new companies as well as regulatory systems.

“It’s a very interesting situation where we have newly legal cannabis in the United States (and) it’s sort of got this perfect storm of strange incentives where you have this new industry of labs—where there’s a ton of these labs with no history or reputations, they’re not established players and there’s not a lot of standardization with procedures—and then all these incentives to report higher THC.”