Cannabis producers in Canada say the process to notify Health Canada of new products is creating needless paperwork and a significant backlog.

The Notice of New Cannabis Product (NNCP) process requires cannabis producers to inform Health Canada of any new products they intend to sell. This notice must be sent to Health Canada at least 60 days before making those products available for sale. Although the process does not officially endorse products, it is intended to give the federal regulator a chance to review the compliance of products prior to reaching consumers.

But many in the industry say the process has become unmanageable for Health Canada, with insufficient employees or infrastructure to manage the thousands of new notifications producers often send in a shotgun effort to get ahead of the bureaucratic curve.

Significant backlog

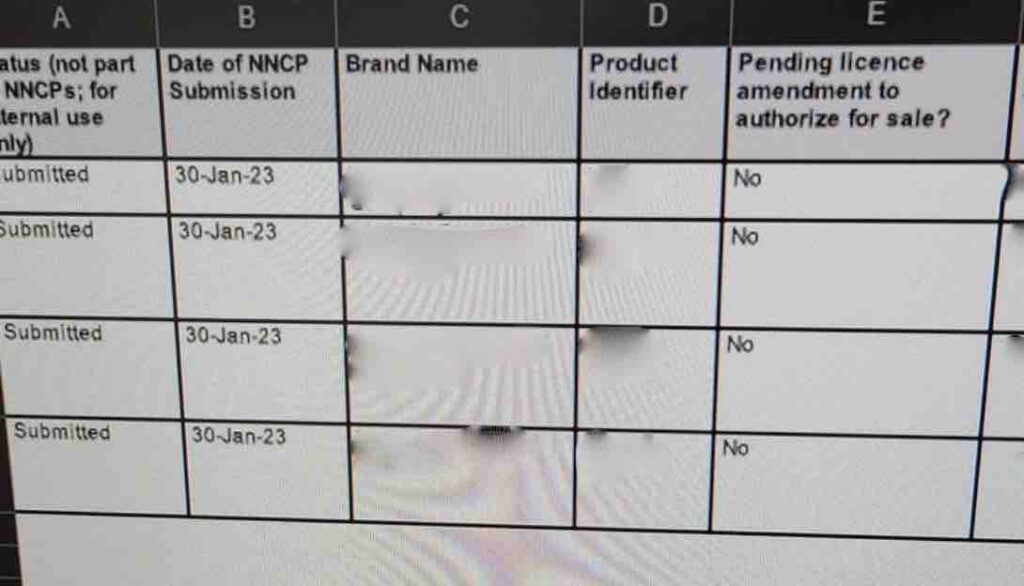

Health Canada tells StratCann that since the regulatory requirement for NNCPs first came into force on October 17, 2019, the regulator has received 86,337 Notices of New Cannabis Product and sent 18,979 requests for more information. These figures are current to April 26, 2023. Health Canada confirmed that eight employees are dedicated to administering this regulatory requirement. This would mean each employee would need to review about a dozen NNCPs per day.

Because of the enormous quantity of NNCPs that come into Health Canada on a daily basis, many products appear to go unnoticed for months, or longer, well after the 60 day notice period has passed and producers have shipped those products off to provincial and/or medical markets.

Health Canada emphasizes that the NNCP process is not an approval process, which means these products can be available to consumers for some time before the federal regulator even notices them.

The most recent high-profile examples of this are the so-called “edible” or “ingestible” extracts: products like lozenges and gummies that some companies had been, in some cases, selling for well over a year before finally being told by Health Canada that they had to take them off shelves for violating the federal 10mg THC limit for edibles.

In a similar issue in 2022, one company was told that their cannabis-infused freezies were not compliant, despite being nearly identical to another product that had been on shelves for about a year prior. Shortly after, the company that made the latter product, Radsicles’ Chill Pops, received notice that they also had to stop selling those products.

Staying true to original names

Jonathan Wilson, the CEO of Crystal Cure, a cannabis producer in New Brunswick, says his company has had to change product names, often several months after they’ve been in the market. Although they didn’t have to pull existing products off shelves, they still had to change product names moving forward, which costs them time and money.

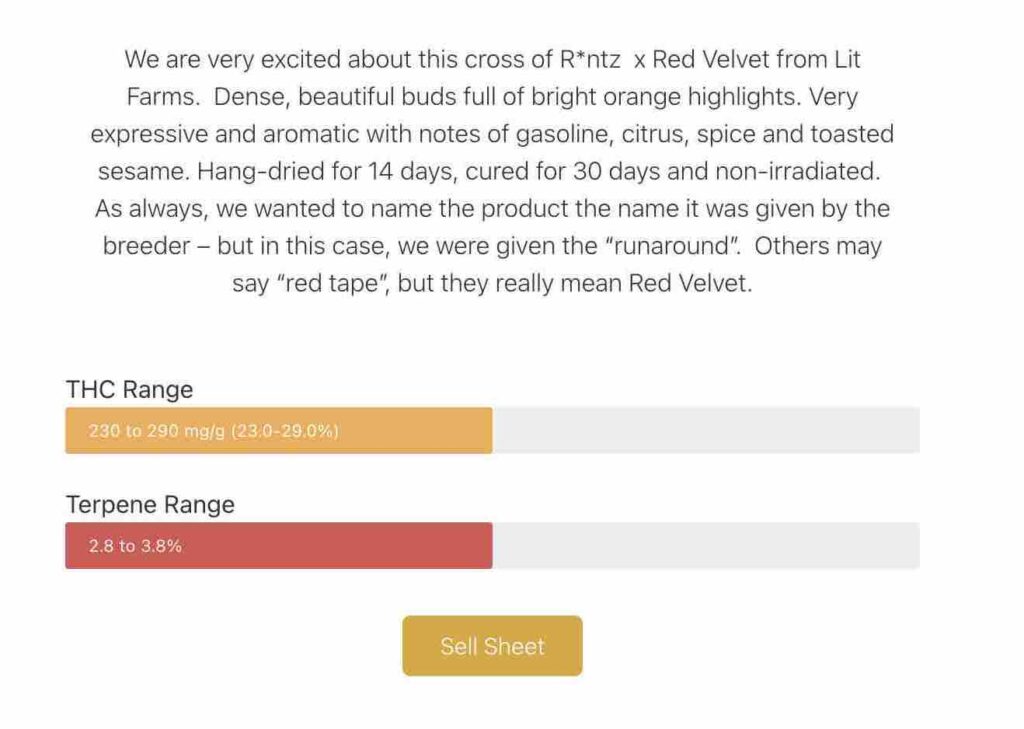

Another problem, he says, is that this can mean being forced to change a well-known “legacy” or black market cultivar name, like Runtz or Wedding Cake, so that they can be compliant with Health Canada’s rules around product names.

In the case of Runtz, he says they ultimately changed the name to “Red Velvet Runaround” to reflect their frustration with the process. But this means they still have to take steps to communicate the original cultivar lineage and name.

“We’ll tell people through other channels what the true name is because part of our story is to give props to the breeder,” says Wilson. “So now we just have to take one more step to tell that story and stay true to the original names and breeders.”

Wilson says he understands why Health Canada needs a process like the NNCP to monitor new products, but he thinks the system needs to be built in a way that takes into account how the industry will always have an incentive to send in numerous iterations of products in advance to save time in getting to market.

“There are only going to be more. We’re all unveiling more kinds of products, and products are getting more innovative. This is not going to get any better as far as the number of products Health Canada will need to deal with. As an industry, that’s good. We want more innovation. So if they can’t handle it now, I can’t see how they will handle it going forward, and you’re going to have a mess of some truly non-compliant products on the market. They won’t be able to keep up and get them out.

“I don’t know if removing the process entirely would work because you’d have things going through that are truly non-compliant. I think cutting down some of the red tape needs to happen. They need to give us, the producers, better assurance that they have reviewed it within the 60 days so we aren’t being told months or even years later that we have to take something off of shelves. That’s not acceptable.”

“There are only going to be more….if they can’t handle it now, I can’t see how they will handle it going forward.”

Jonathan Wilson, Crystal Cure

Benny Presman, the founder and president of Weed Me, an Ontario-based producer with hundreds of different products on the market, says part of the problem with the process is simply that Health Canada is overwhelmed with submissions. While the process is a 60-day notice, he says his company has been told to change product names or branding after months, or even a year, of them being available for sale.

Too much paperwork

“There are so many NNCPs. I think the process should be changed somehow. We don’t necessarily send many in, but speaking with others in the industry, as soon as they get an idea they will send every option and format to Health Canada.”

He doesn’t blame his colleagues who take this approach. It’s just a byproduct of how the system is built and part of why he thinks the regulator needs to revisit the process.

One cultivar name they had to change was a traditional name, “Goliath,” which they ultimately had to rename as “Go Lie Eth,” then to “Goliat” (as a different LP got an approval under this name) and eventually to “Oliath” because Health Canada deemed the original name as a character from the Bible—the Cannabis Act does not allow products to depict a person, character, or animal, whether real or fictional.

Weed Me also had to deal with a name change for a Wedding Cake vape that had been available for around a year before they were told to change the name.

Like Wilson at Crystal Cure, he says their goal is paying homage to the original cultivar names.

“We want to stay true to the original strain name. That’s our main priority and why we do this.”

Although they have never faced any demands to pull products from shelves, even renaming products costs time and money, something companies in this space don’t always have.