| COMPANY: | Annapolis Valley Craft Cannabis |

| LICENCE TYPE: | micro cultivation |

| APPROACH: | Outdoor, native soil grown |

| TIMELINE: | ~10 months (March 2019 to January 2020) |

| COST: | Approximately $70,000 |

| FACILITY: | Outdoor, small farm |

Adam Webster, his father Donald, and his mother Deenie started Annapolis Valley Craft Cannabis as a way to better utilize their relatively small plot of farmland in north western Nova Scotia, just off the Bay of Fundy.

Adam’s family have been growing fruits and vegetables of all kinds on the land since Donald’s parents bought it in the 1940s, and currently Adam manages a market garden for local farmers markets, as well as a CSA with twenty members.

As they’ve developed their market garden, Adam says he and his family were looking at other ways to add value to the farm, utilizing their unique piece of land.

“We looked at grapes but there’s a lot of upkeep to that and it didn’t suit the philosophy of growing things more naturally. When this came along and allowed for smaller acreage and higher revenue, and went along with our philosophy of doing things organically, we thought we could manage it well just among the family members here,” explained Adam.

Their family farm is just one of many like it all across the Annapolis Valley, a region known for warmer weather and better farming than other parts of Nova Scotia.

“The Annapolis Valley is a real hidden gem in Canada,” says Adam’s father Donald. “It’s similar to the Niagara region, it’s similar to the Okanagan. There’s every kind of orchard fruit produced here, there’s chickens, eggs, beef, there are wineries that started twenty, twenty-five years ago now, there’s a winery tour bus through the valley. There’s a high concentration of farms here and a great community.”

“I think there are a lot of farms that are interested in it and other farmers have come through looking at ours, so I think the micro side of it will continue to grow. And I think that the large, indoor growing facilities may struggle with the overhead cost that they have. And the industry is just starting, and so much debt is a hard way to go.”

Donald Webster

Adam, who manages the farm, says he thinks these unique factors makes it an ideal place for outdoor cannabis, especially on a small scale.

“It’s kind of a micro climate, so it’s a lot warmer than surrounding areas and the soil is a very fertile, very sandy soil which you don’t find in a lot of Nova Scotia.”

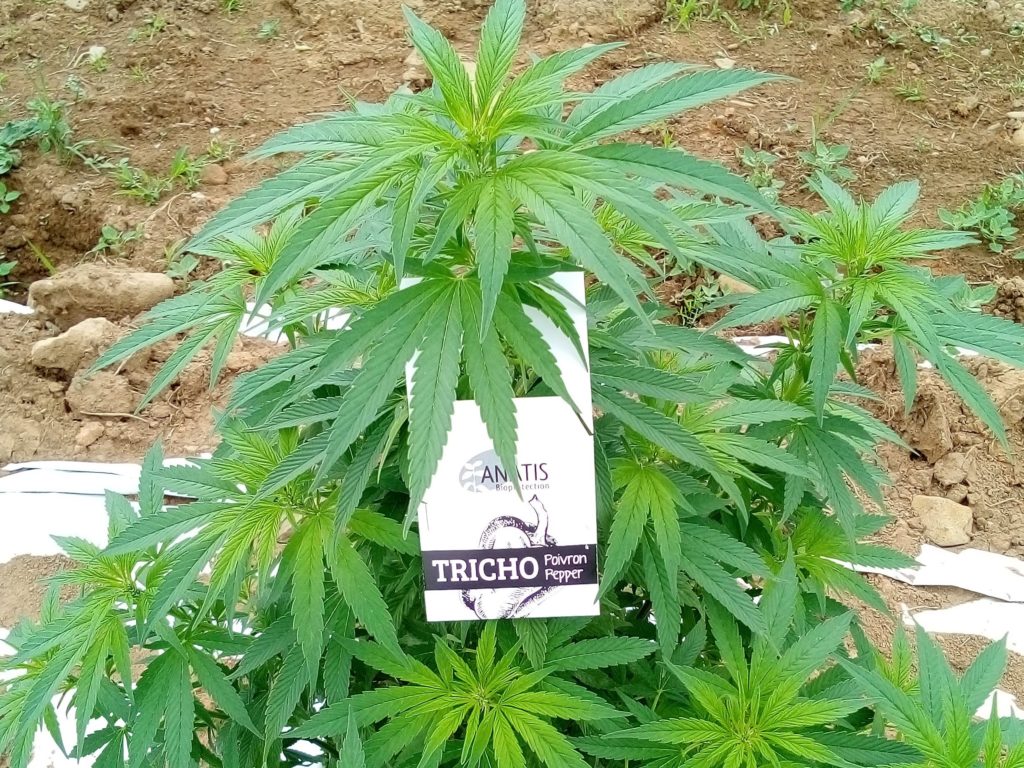

His approach to cannabis, he says, is the same as his approach to everything else he is growing on the farm, utilizing cover crops, crop rotation, interplanting, and beneficial insects.

“We’re trying to grow cannabis the same way we do our vegetables,” explains Adam. “Which is as naturally as possible using predatory insects and natural fertilizers like alfalfa meal, and we’re just growing it outside in the sun and soil. We’re growing peppers and tomatoes in with our cannabis.”

His hope is that this will translate into a unique product they can market locally in their own province.

“We’re trying to grow cannabis the same way we do our vegetables, which is as naturally as possible using predatory insects and natural fertilizers like alfalfa meal, and we’re just growing it outside in the sun and soil. We’re growing peppers and tomatoes in with our cannabis.”

Adam Webster

“There’s not a lot of outdoor, native soil grown cannabis products out there,” says Adam. “It’s almost all inside, hydroponic, high impact, and from what we hear there’s a demand for something grown outdoors with a lower impact. So we’re hoping that we can go to the province here in Nova Scotia and they’ll have an interest in supporting our local, outdoor product. But if not, obviously we’re open to other provinces too.”

“We’d like to sell local because there’s a lot of interest in Annapolis Valley Product,” adds Donald, “so we really want to grow and sell right here.’

Because they only have a cultivation licence, the farm is currently working with Craft Depot, a broker who connects cultivators and processors. Their expectation is that their first harvest will be in early September, with product in the form of dried flower potentially available by the winter.

Adam says he is looking at a nursery licence, both to supply clones for his own cultivation licence but also potentially to supply to consumers. His ideal, he says would be able to sell them directly to people on site.

“I think people will be interested in getting clones,” he says. “If we can ever sell right to the gate, then I think a lot of people would come in the spring to buy their four clones for the summer. I think there’d be a lot of interest in that.”

He says he is also excited to share some of the unique genetics they were able to bring in at licensing, including what he describes as a cross between a G13 and an Iranian landrace, that allows for a harvest in late August or early September. This is one of several they are currently growing this season and hope to have to market before the end of the year.

“I think people will be interested in getting clones. If we can ever sell right to the gate, then I think a lot of people would come in the spring to buy their four clones for the summer. I think there’d be a lot of interest in that.”

Adam Webster

One challenge, Donald says, is the licensing process. Because they did the majority of the application themselves, with Adam and his wife Courtney building their SOPS and filing under the CTLS, the process at first was daunting. But he says ultimately they pushed through and found that once they were in the process, Health Canada was receptive to assisting them getting to the licence stage.

They originally applied in March 2019, but had to change several aspects of their licence over the summer and then submitted their first video evidence package in August 2019 and their second in November. They were issued their licence in early January of this year.

“It’s such an arms length relationship at first, you just sort of have to take it on and figure it out as you go,” he explains. “But once you do make contact with them and over a series of conference calls, you realize they are there to help and you’re both working toward the same goal. I know a lot of folks take an adversarial view of the relationship, but I think if you realize they have a job to do and have to keep things safe, then it’s not that they are there to stop you.”

Still, Adam says there were a lot of things Health Canada didn’t understand about their approach to growing cannabis that made the application process probably take a little longer.

“They didn’t understand a lot of growing practices, things like cover crops or rotating crops, and we had a lot of back and forth on that. But they did eventually seem to understand,” he explains. “But going through the whole process of getting everything into the CTLS website is daunting for somebody to just jump in and navigate themselves.”

Donald estimates they spent about $70,000 getting their farm ready for licensing, including erecting a ten foot deer fence, bringing in and retrofitting two SeaCans to serve as drying, curing, trimming, storage, and office space, plus licensing fees, security clearance, and local administrative fees.

The elder Webster says he thinks the model is one many other farmers in the Annapolis Valley are looking at, especially if his family’s farm can prove it works. He knows some who have already applied, and he expects others may soon follow.

“I think there’s lots of farms that are considering it and lots who are in the process of getting there,” says Donald. “There are a lot of farms that are interested in it and other farmers have come through looking at ours, so I think the micro side of it will continue to grow. I think that the large, indoor growing facilities may struggle with the overhead cost that they have. And the industry is just starting, so much debt is a hard way to go.”